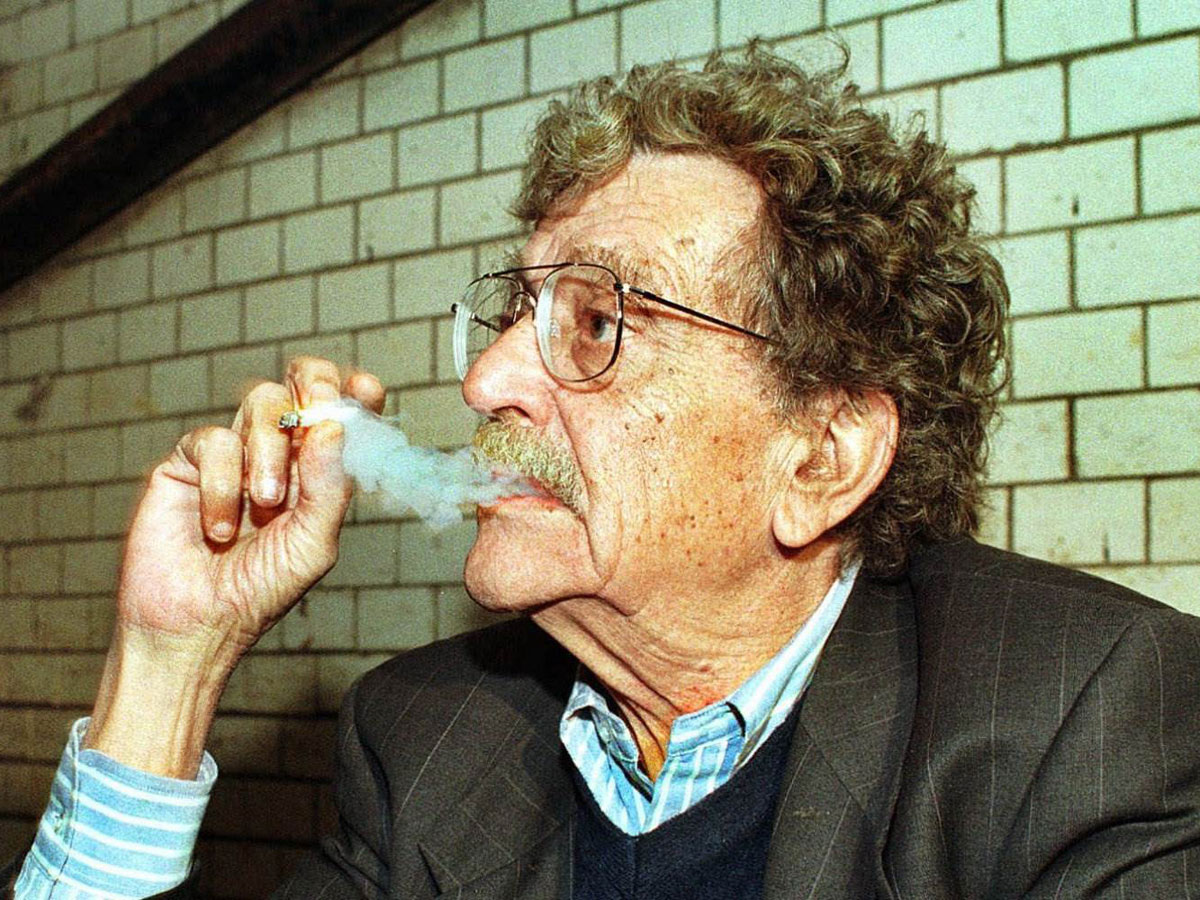

We have lost a truly amazing American thinker–a man who could make social commentary both hysterical and utterly heartbreaking. He was an original voice who, despite his advanced age, drew in eager college kids and young adults easier than an all-you-can-drink kegger or a night of free Spinal Tap.

Aside from reading just about everything the man wrote, I, along with my classmates, had the honor and privilege of having Mr. Vonnegut be our commencement speaker. Sure, we could have had a head of state or some weird administrator from The Red Cross, but instead we had an old guy from Indianapolis who happened to be the best, and most insightful commencement speech writer of all time.

The man was even cool enough to hang out the night before graduation at a family drinking and eating event at the University. He probably wanted to rethink accepting that invite after a friend of mine, while following him up the steps to the bathroom, uttered, “Hey, I loved you in Back to School!” Vonnegut turned, gave us a sly smile and continued walking.

Here, in its entirety, is the speech he gave that day:

There are three things that I very much want to say to the Class of 1994 in this brief hail and farewell. They are things which haven’t been said enough to you freshly minted graduates nor to your parents or guardians, nor to me, nor to your teachers. I will say these in the body of my speech, I’m just setting you up for this.

First, I will say thank you. Second, I will say I am truly sorry – now that is the striking novelty among the three. We live in a time when nobody ever seems to apologize for anything; they just weep and raise hell on the Oprah Winfrey Show. The third thing I want to say to you at some point – probably close to the end – is, “We love you.” Now if I fail to say any of those three things in the body of this great speech, hold up your hands, and I will remedy the deficiency.

And I’m going to ask you to hold up your hands this early in the proceedings for another reason. I first declare to you that the most wonderful thing, the most valuable thing you can get from an education is this – the memory of one person who could really teach, whose lessons made life and yourselves much more interesting and full of possibilities than you had previously supposed possible. I ask this of everyone here, including all of us up here on the platform – How many of us, how many of you, had such a teacher? Kindergarten counts. Please hold up your hands. Hurry. You may want to remember the name of that great teacher.

I thank you for being educated. There, I’ve thanked you now; that way I don’t have to speak to a bunch of nincompoops. For you freshly minted college graduates, this is a puberty ceremony long overdue. We, whose principal achievement is that we are older than you, have to acknowledge at last that you are grown-ups, too. There are old poops possibly among us on this very day who will say that you are not grown-ups until you have somehow survived, as they have, some famous calamity – The Great Depression, World War II, Vietnam, whatever. Storytellers are responsible for this destructive, not to say suicidal, myth. Again and again in stories, after some terrible mess, the character is able to say at last, “Today, I am a woman; today I am a man. The end.”

When I got home from World War II, my Uncle Dan clapped me on the back, and he said, “You’re a man now.” So I killed him. Not really, but I certainly felt like doing it.

Now you young twerps want a new name for your generation? Probably not, you just want jobs, right? Well, the media do us all such tremendous favors when they call you Generation X, right? Two clicks from the very end of the alphabet. I hereby declare you Generation A, as much at the beginning of a series of astonishing triumphs and failures as Adam and Eve were so long ago.

I apologize. I said I would apologize; I apologize now. I apologize because of the terrible mess the planet is in. But it has always been a mess. There have never been any “Good Old Days,” there have just been days. And as I say to my grandchildren, “Don’t look at me. I just got here myself.”

So you know what I’m going to do? I declare everybody here a member of Generation A. Tomorrow is another day for all of us.

Having said that, I have made us, for a few hours at least, what most of us do not have and what we need so desperately – I have made us an extended family, one for all and all for one. A husband, a wife and some kids is not a family; it’s a terribly vulnerable survival unit. Now those of you who get married or are married, when you fight with your spouse, what each of you will be saying to the other one actually is, “You’re not enough people. You’re only one person. I should have hundreds of people around.”

I met a man and a wife in Nigeria – Ibos. They just had a new baby. They had a thousand relatives there in southern Nigeria, and they were going to take that baby around and visit all the other relatives. We should all have families like that.

Now, you take Dan and Marilyn Quayle, who imagine themselves as a brave, clean-cut little couple. They are surrounded by an enormous extended family, what we should all have – I mean judges, senators, newspaper editors, lawyers, bankers. They are not alone. And one reason they are so comfortable is that they are members of extended families, and I would really, over the long run, hope America would find some way to provide all of our citizens with extended families – a large group of people they could call on for help.

Now, I’ve made us an extended family. Does our family have a flag? Well, you bet. It’s a big orange rectangle. Orange is a very good color and maybe the best one. It’s full of vitamin C and cheerful associations, if one could forget the troubles in Ireland.

Now this gathering is a work of art. The teacher whose name I mentioned when we all remembered good teachers asked me one time, “What is it artists do?” And I mumbled something. “They do two things,” he said. “First, they admit they can’t straighten out the whole universe. And then second, they make at least one little part of it exactly as it should be. A blob of clay, a square of canvas, a piece of paper, or whatever.” We have all worked so hard and well to make these moments and this place exactly what it should be.

Now, as I have told you, I had a bad uncle named Dan, who said a male can’t be a man unless he’d gone to war. But I had a good uncle named Alex, who said, when life was most agreeable – and it could be just a pitcher of lemonade in the shade – he would say, “If this isn’t nice, what is?” So I say that about what we have achieved here right now. If he hadn’t said that so regularly, maybe five or six times a month, we might not have paused to notice how rewarding life can be sometimes. Perhaps my good uncle Alex will live on in some of you members of the Syracuse Class of 1994 if, in the future, you will pause to say out loud every so often, “If this isn’t nice, what is?”

Now, my time is up and I haven’t even inspired you with heroic tales of the past – Teddy Roosevelt’s cavalry charge up San Juan Hill, Desert Storm – nor given you visions of a glorious future – computer programs, interactive TV, the information superhighway, speed the day. I spent too much time celebrating this very moment and place – once the future we dreamed of so long ago. This is it. We’re here. How the heck did we do it?

A neighbor of mine, I hired him – he was a handyman – to build and “L” on my house where I could write. He did the whole damn thing – he built the foundation, and then the side walls and the roof. He did it all by himself. And when it was all done, he stood back and he said, “How the hell did I ever do that?” How the hell did we ever do this? We did it! And if this isn’t nice, what is?

I got a letter from a sappy woman a while back – she knew I was sappy too, which is to say a lifelong Democrat. She was pregnant, and she wanted to know if I thought it was a mistake to bring a little baby into a world as troubled as this one is. And I replied, what made being alive almost worthwhile for me was the saints I met. They could be almost anywhere. By saints I meant people who behaved decently and honorably in societies which were so often obscene. Our own society is very frequently obscene. Perhaps many of us here, regardless of our ages or power or wealth, can be saints for her child to meet.

There was one thing I forgot to say, and I promised I would say, and that is, “We love you. We really do.”