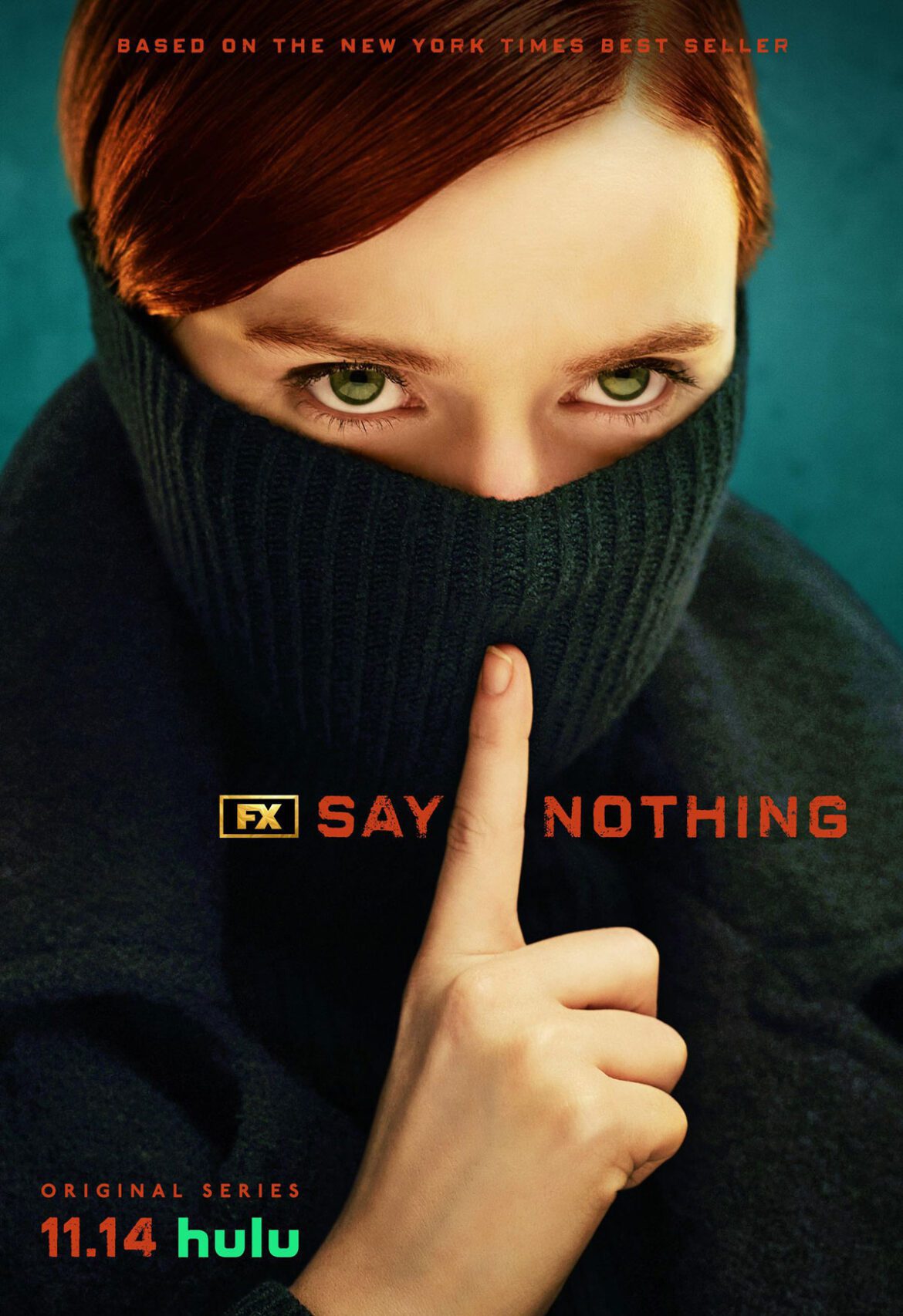

Service: FX on Hulu

Series Year: 2024

Watch: Hulu

My first piece of advice with Say Nothing is to turn on your closed captions. I’ve been to Ireland a couple times and didn’t find most folks’ accents too difficult to unwind. However, this is Northern Ireland, and it’s a totally different game. And, trust me, in a series where there is a lot of talking — despite it being called Say Nothing — you’ll not want to miss a single word. Because the series spreads itself out over three decades of the The Troubles, which somehow didn’t end until 1998. Which wasn’t something I knew or remembered because I was too involved with being a young person in NYC finding the best happy hours and trying to stretch eggs, pasta and hot dogs to their limit. So, my troubles were hardly theirs, but bombings in Ireland just didn’t register with me at the time. So this was not only an entertaining series, but a learning experience for me as well.

Fictionalizing — or semi-fictionalizing — history is tough. You’re going to add flare where there is none. You have to put dialogue in the mouths of people who never said what you have them say. And, in some cases, you’re going to essentially accuse people of being terrorists who claim they were never terrorists. Such is the claim of one Gerry Adams, who the series depicts as the head of the IRA, but then has to stick a disclaimer at the end of every episode: “Gerry Adams has always denied being a member of the IRA or participating in any IRA-related violence.” I mean… what are we doing here? While true that Adams has denied any involvement with the IRA, the entire nine-part drama hinges on him being the leader of what amounts to an insurgency (which is how the Irish would look at it) or a terror organization (which is how the English government would view it). It’s clear where the creators of the series sit with this, but there’s this winking legal asterisk that they have to stick on the end that seemingly adds more fiction to the historical fiction. Or at least to the satisfaction of Adam’s lawyers. Because, if the book on which the show is based has anything to say about it, Adams is full of shit.

The series in itself is almost like two shows in one. The first half shows the exuberance and verging-on-sexy energy of young people rebelling against the evil empire. It has a real Star Wars vibe. But with better music and clothes. And even some dark comedy. It almost has a Guy Ritchie thing going on. The perspective is super-narrow, focusing on a young Dolours Price (Lola Petticrew), her sister, Marian (Hazel Doupe), and the IRA leadership duo of Adams (Josh Finan) and Brendan “The Dark” Hughes (Anthony Boyle). Coming from a historically activist family — including an aunt with whom they lived who lost her eyes and hands handling IRA bombs — Dolours forewent a seemingly promising run at university to join Hughes in the IRA. Also following in her family’s footsteps was her younger sister, Marian. The story is told in a really insular way, so it’s tough to understand the numbers within the IRA, but the sisters are portrayed as a bit of an outlier in terms of their level of involvement as very young women in the struggle — along with their quick ascent directly to the leadership class with Hughes and Adams. The tone of the show is a bit swashbuckling and exciting and young and even a bit sexy. Fighting the faceless British cops and soldiers, bombing stuff and generally causing chaos and upheaval. Again, we really zoom in on them and have very little in the way of understanding scale or impact of the actual British occupation on the Northern Irish population. Granted, it’s “cool” until it isn’t.

The second half of the series is more about repercussions of said youthful activities. Even if said activities include murder and maiming, among other things. When the chickens come home to roost, so to speak. The turning point being an entire episode where the sisters, after being arrested for a bombing in London, undergo a brutal hunger strike. To be honest, the episode is borderline unwatchable. Just scene after scene of tubes being stuck down their throats and the sisters becoming weaker and weaker as they head to their inevitable death from starvation. I mean, it’s probably good art, but tough TV. And suddenly the sexy plotting and music and all the rebel energy goes away and we’re in the aftermath. As Dolours meets and marries actor, Stephen Rea. And is continually haunted by her past victims, while her drinking and mental state spiral. Same with Brendan Hughes, who has become a tired shell of his former self. All while Marian doubles-down on her dedication to the seeming lost cause and Adams — still denying his past actions, and in doing so gaining legitimacy — becomes the public face of the peace agreements.

All while we re-focus on the disappearance case of one Jean McConville, who is among the “disappeared,” the group of sixteen Northern Irish citizens who were seen as spies or traitors to the cause, vanished and were presumed murdered and buried somewhere in Ireland. I kind of get what they were going for here, but the dramatic shift to her case in 2003 kind of felt a bit tacked on. They do address it earlier in the series and circle back to it in relation to Dolours and Marian, but so much happens between McConville’s abduction in 1972 and the search for her body, it’s kind of tough to feel that emotional pull and connection that I think they were going for. McConville was a mother of ten, after all, and was disappeared from her apartment, leaving all of her children to fend for themselves until child services finally came along and broke up the family. I think this was the attempt to balance the perception that they set initially with the series that somehow what the IRA folks were doing was 100% altruistic and not, like a lot of other strong-armed insurgencies, paranoid and sometimes antithetical to its own mission at its core. In other words, not everything was cool young people fighting the evil empire. Sometimes they were also bad actors in their own struggle. It’s that dichotomy that tore Dolours apart inside and made this series a compelling and worthwhile watch.