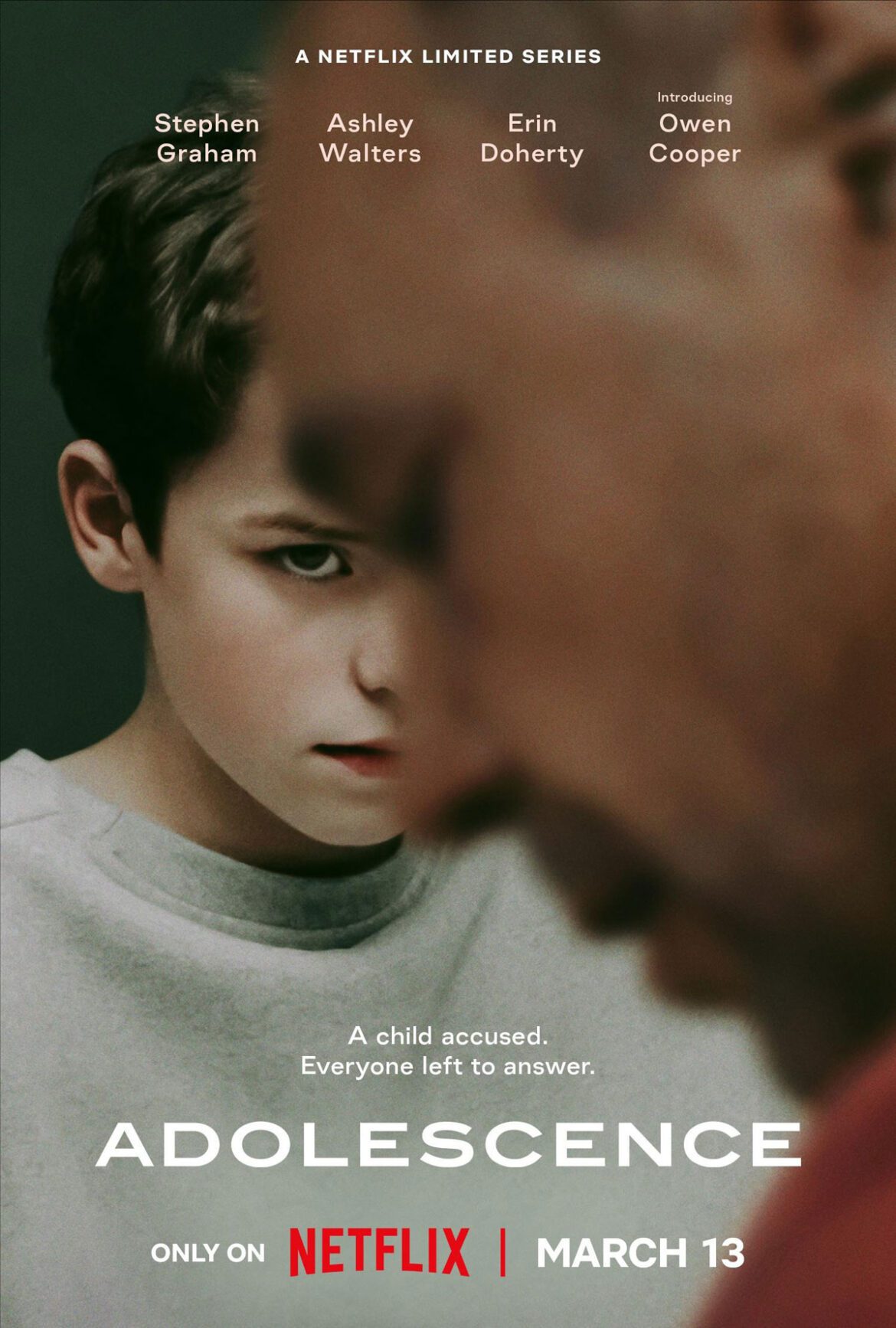

Service: Netflix

Creator: Stephen Graham

Jack Thorne

Series Year: 2025

Watch: Netflix

I feel like I’m at a point where I don’t understand what people like. Or why they like it. Other than the fact Netflix is ubiquitous and now incredibly expensive. Meaning when something like Adolescence enters the zeitgeist, the millions of Netflix subscribers feel they need to get their money’s worth. So they jump in with both feet and can make something that would otherwise seem challenging and not necessarily like a mainstream “hit” — like a Baby Reindeer — a hit. That series was super-disturbing and hardly the multi-camera fair of a Big Bang Theory or even the cheesy procedural goofiness of a C.S.I. You know, the stuff that used to qualify as popular television hits. Well, here’s another truly dark series that people are all over, praising it to high heaven. But — and I know I’ll catch shit for this — is it maybe, just maybe, the latest in Netflix group-think and bandwagon-jumping that permeates the new media landscape?

Let’s get it straight, this show is a technical marvel. Each one of the four, hour-long episodes is done in one, long shot. I looked for edits, but didn’t notice any obvious cuts. I can’t even imagine the planning and coordination that it took to get that done. Frankly, it’s pretty mind-boggling. Which in and of itself is incredibly impressive, but in some ways also distracted me from the narrative. Because I kept thinking, “How the heck are they going to get from here to there to continue the story?” Because the cameras had to physically travel from place to place without cutting. Turns out that when they needed to move locations, they transferred shots to drones somehow and basically flew us there. Or had some overly-long (and somewhat boring) driving scenes where not a whole lot happens. But there are some distances that were obviously too far for this technique and I think they, in some ways, drove themselves into a cul-de-sac with the single-shot conceit. So, what was the most remarkable aspect of the show was also its most limiting. And, for me, caused some scenes to seriously drag.

Beyond the filmmaking the story here is modern and entangled with our current political moment. It is a fraught time for young males in society, and this series attempts — in its small way — to address it. But it doesn’t, really. The show becomes more about the aftermath of a crime. The affect on the family of a child committing a horrendous act. That act, though, was seemingly rendered inert by the construct of the series, which sapped the power of its message. Which ultimately may not have been what the show creators were trying to explore in the first place. And this is where people and critics layered on meaning and exploration on this show that wasn’t really there. They extrapolated this narrative about the manosphere and masculinity that was certainly touched on as part of our crime, but is was sprinkled in in a way that felt cursory. Like it didn’t go much deeper than a what you might find in a short NYT article on the subject.

At the heart of the crime is a young man who stabs his female classmate to death because… she basically called him an incel. Which, at thirteen, doesn’t really jibe with the definition of what an incel is. At thirteen, many boys are either pre-pubescent or just kind of hitting that point in their maturity. There is zero expectation that a pre-pubescent boy is hooking up with girls. You are not “celibate.” By choice or not. You are a child. It’s not that there aren’t 13-year-old boys having sex, but by the looks of these pasty-ass English lads on this show, none of them is coming within 10 feet of a live female human being. So the fact this boy — whose only previous “crime” involved posting some photos of female models on his Instagram and making some dumb 13-year-old-boy comments about them — goes from enjoying photos of pretty ladies to a little bit of ignorant cyber-bullying to all-out psychotic murderer is a bit of a leap. And without the series really diving into the cause in an intellectual and considered way, it leaves us to believe that society has made monsters of every hormonal teen. That they’re all just ticking, murderous time bombs ready to explode at the first online slight from a girl they might like. The whole motivation and crime didn’t track for me; it felt undercooked.

Where the show really shines a light is on the aftermath of this shocking murder on the boy’s family. I don’t think it felt incredibly different than other melodramas about family tragedy, but the acting is pretty top-notch. Especially young Owen Cooper, who had no former professional experience anywhere at this level. And, for the first time in a long time, a production actually hired a 13-year-old boy to play a 13-year-old boy. It was refreshing. And, yes, the parents’ confusion, and the anger and sadness of the father, played by creator, Stephen Graham, is harrowing. We’re let into the fact the father does have a temper that he occasionally loses, but that’s certainly not enough to create a murderous son. But also society doesn’t make every boy a murderer. So why does this kid murder? Seems he’s just wired that way. Which begs the question: if it wasn’t this slight by some random girl and some ribbing from his classmates, would it eventually have been a teacher who failed him? Or a boss who gave him a bad work review? Or a girlfriend who broke up with him? Or someone who gave him a dirty look on the street? It’s just, based on this plot, one plus one doesn’t equal two. His father is repulsed that he’s raised a monster. But also guilty that he had something to do with creating this monster. But, really, this is a nature over nurture thing. Nobody created this murderer — he just is.

Last thing: I swear. Hipster Mom watches a lot of TV. She is especially a fan of anything and everything similar to Perry Mason. She is that television viewer I mentioned way back at the beginning of this review. A typical Boomer who feels everything is a procedural and necessitates clear “aha!” resolution. I talked to her about this series and she was convinced that there should be a part two where they show the trial and something is uncovered that he somehow didn’t murder the girl. Because television has created Law & Order brain out of the viewing public. I pointed out that we see him murder the girl on CCTV and that this isn’t a mystery or police procedural and that it wasn’t the point of the series to unmask the “real” killer. The kid killed the other kid and that’s not in question. It’s about the affect of this unexplainable violence on a community and the family of the heretofore innocent, angel-faced boy. She really liked the show, but still couldn’t get past the fact there wasn’t a question about the murder and insisted we needed a part two to figure it out. I imagine she is not alone. So, perhaps the popularity of this series isn’t for the reason the creators and Netflix and the critic class think. It could be because the viewing public’s brains are broken by the narrative modality of modern TV and think they’re watching something they’re totally not watching.