Author: David B.

Publication Year: 2002

Length: 368 pages

I learned a little bit about the art of the graphic novel through Chris Ware and his Jimmy Corrigan: The Most Fuckin’ Depressing Kid on Earth. Who knew comics could do anything beyond showing chicks in giant breastplates and dudes in capes and tights? And don’t even get me started on Family Circus.

My second dive into the “serious” graphic novel came courtesy of my book club at work, and this little selection, which was originally published in French. I know you’re saying to yourself, “Damn, a comic book about a French kid and his epileptic brother, and the effect of his illness on his French family (who, by the way, speak French)? Sign me right the hell up!” Despite sounding like the winning answer to the challenge, “Name the most god-awful reading experience you could possibly imagine,” this thing was actually a decent approximation of the wacky autobiographical slice of life memoir that we’re all used to reading. The closest novel I can think of in terms of comparison would be Running With Scissors. Granted, there are no drawings in that book, but both deal with the familial drama in a way that makes the horrific reality of their situation a little more bearable for the reader by interjecting a sense of humor about their lives.

Here, our protagonist, David B., is the unfortunate victim of his older bother’s severe epilepsy. At some point their crew was a normal French family with three kids (two sons and a daughter), with the sons running around the alleys of their town playing and just being boys. And then the fits start. The neighborhood kids, who once thought of the local Muslim dude as the boogeyman, now regarded David’s brother as the pinnacle of evil. Obviously it was just kids being kids, but the impact was swift and immediate. Their parents took their son to doctors to determine what the issue was. And when the doctors couldn’t do anything for their son, they went to a healer. And when the healer couldn’t help them, they moved onto a macrobiotic commune, and then put their son in the hands of any number of gurus and swamis and mediums and whatnot, each time uprooting the family and involving their other two children in whatever the latest treatment happened to be going on for their sick son.

All the while, David B. fought with his loneliness and isolation. He knew nobody and had nobody to talk to about how his brother’s illness was destroying his life. Through amazingly detailed illustration David shows what is going on in his mind–all the weird invisible bird-headed friends he invented in his brain all sketched in his drawing journal. He struggles with black thoughts of his brother’s death, and the guilt he sustains in sometimes wishing him harm. He almost can’t take the embarrassment at his brother’s reluctance to even stick up for himself against his little brother, or the lack of will to do anything with his life.

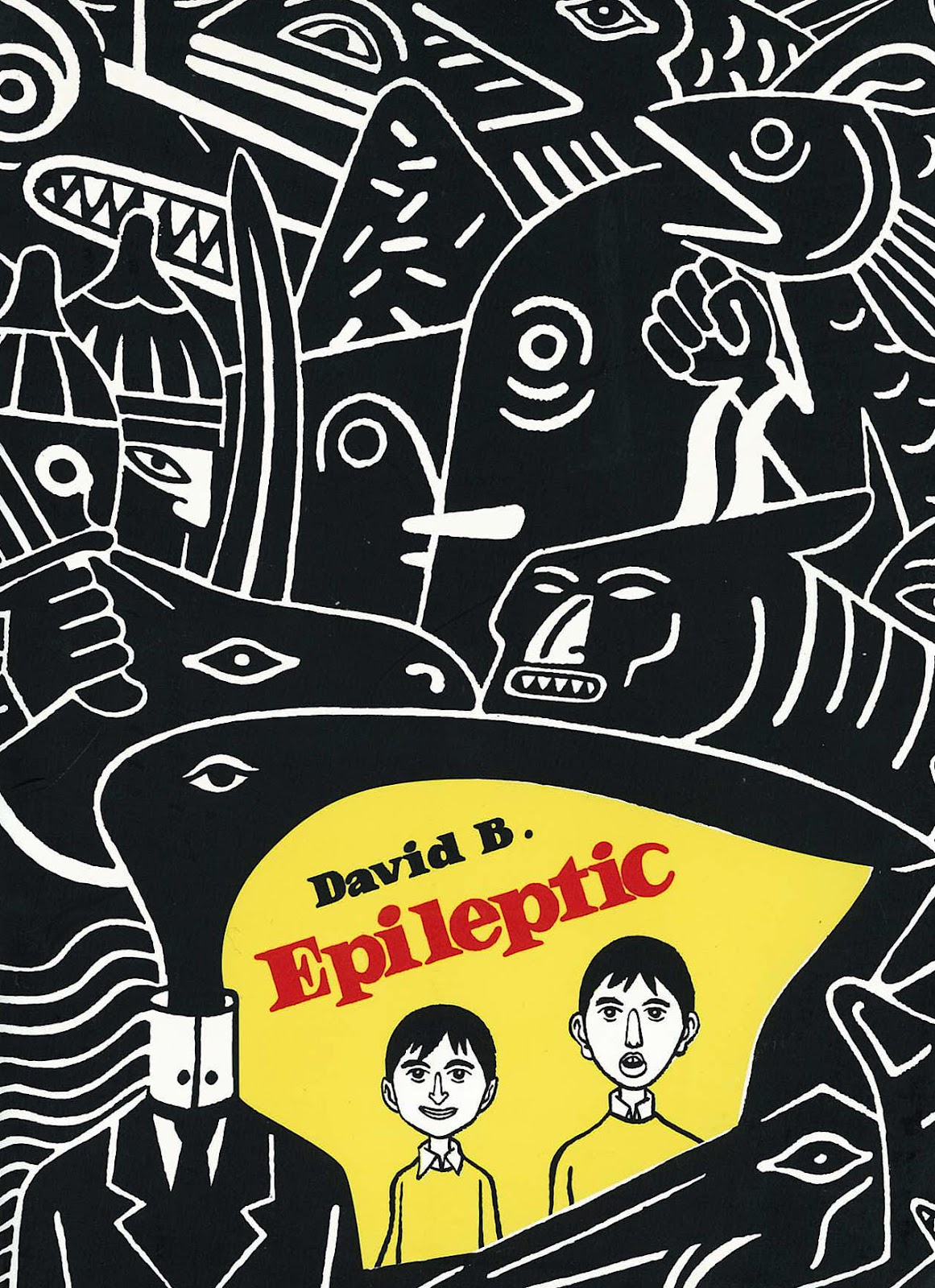

I honestly don’t know a lot about illustration, but I can imagine that this stuff took absolutely forever. The drawings are intricate and complex and really amazing to look at. There stuff is very totemistic and Egyptian God-like. There are swirling ghosts and faces in the back of every illustration. And, amazingly, the story is compelling in its weirdness for the very fact that the illustrations add a layer that wouldn’t otherwise be there in a traditional novel. Sure, the great dialogue you’d see in a normal memoir isn’t quite as strong when being presented in speech bubbles, but the peek into David’s dark and confused mind via his art more than makes up for it.

For any folks out there biased against the art of the graphic novel, know that I too thought not long ago that only the mentally deranged and kiddie-touchers bought these wacky comic books. Now I know that the right authors can work magic with their pens, and can tell a fully fleshed out story that can be both deep and intriguing.