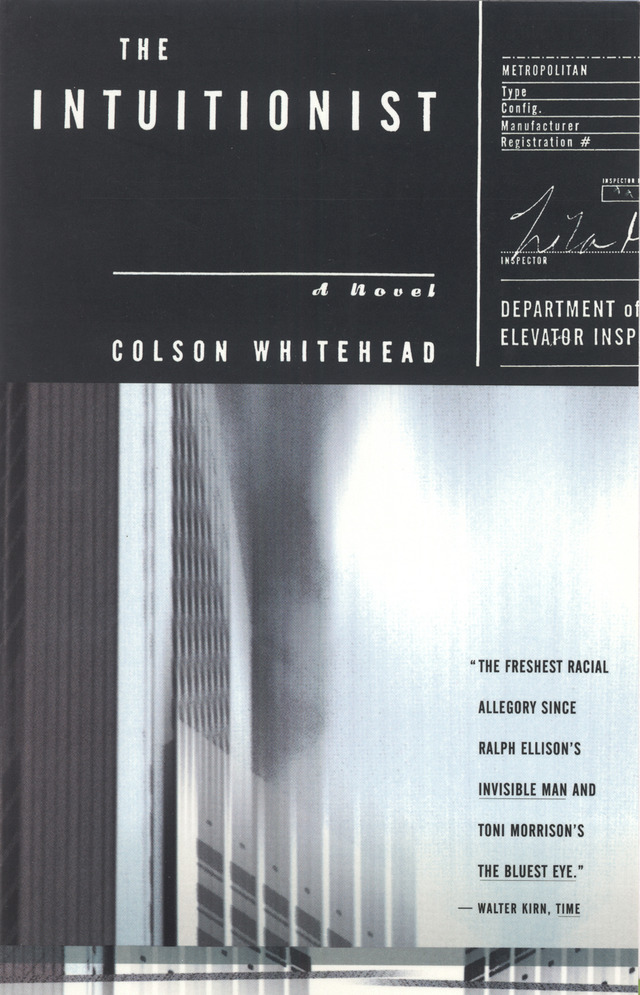

Author: Colson Whitehead

Publication Year: 1999

Length: 255 pages

I’ve heard this type of fiction called “fantastic realism” in recent years. Although I’m not sure that really fits in this case. Maybe, as in the case of another recent read, The Castle In the Forest, or more accurately, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, we can categorize this one as a revisionist history. But even those don’t fit the non-world that The Intuitionist inhabits. Sure we recognize the surroundings as mid-century Manhattan, but this is a time and place when the idea of elevators, and their bureaucracy, somehow holds a position of hierarchy in the city government that I don’t believe is, or ever was, that big of a thought in anybody’s head.

And this is the theme, and the high concept idea, that our author hangs his hat–and the whole foundation of the book–on. Buy that and you’ll buy the story. Think it’s a stretch and the whole thing turns into a farce. The root of the idea is that cities like Manhattan wouldn’t exist without verticality and men like Otis and his subsequent impact on the whole elevator (and to a lesser extent escalator) industry. There’d ne no skyscrapers, no symbols of industry, no gods lauding over the city in their glass towers. The city would be short and brutish. Except this concept is but a mere framework to tell the tale of the city’s first (and only) black woman elevator inspector. You see this isn’t really a book about elevators and the development of the modern city, but an allegory on race and gender.

Now I’m hardly smart enough to unravel the subtext and underlying message behind Colson (who is himself African American) making Lila Mae fight the all white elevator inspector union in her bid to clear her name in an accident in one of the buildings she inspected, but I do understand the idea that things in the world have not always been good for women and people of color. So Colson has created this alternate Manhattan that revolves around politicians, elevator inspectors and the tyrannical elevator corporations themselves, all of whom are for the most part cigar chomping white men. There are entire universities dedicated to the study of elevator inspection, ivy-covered places of higher learning filled with white students interested in pursuing pensioned union jobs maintaining cities. Like any serious area of study, there are two different philosophies: empiricism and intuitionism. The empiricists are the old school folks who look at an elevator, test its ball bearings (or whatever) and make their calls based on what can be poked, prodded and measured. The intuitionists close their eyes and trust their feelings, the sounds they hear and the feel of the ride. These apposing philosophies form the basis the political divide in the city, as well as the trust and distrust in the old guard of the elevator inspector’s union.

Our protagonist, Lila Mae, falls squarely in the intuitionist camp, and unfortunately because of her gender and race makes a perfect patsy in the empiricist’s plot to discredit her, and in doing so discredit the intuitionists as a whole in a battle for City Hall. The elevator crash and failure at one of her buildings seems suspicious (he having a perfect record), and is especially suspicious during a heated campaign for mayor and elevator commissioner. It’s now up to her to uncover the conspiracy, clear her name and in doing so resurrect the reputation of all intuitionists. Her search for the truth leads her down many a dark alley filled with bribery, intimidation and the possibility of an intuitionist black box only rumored to be the life’s work of intuitionism’s founder. She also runs up against the white establishment and their operatives, who hold sway over even people of her own race.

The book basically ends up being a well-written treatise on race wrapped up in the guise of an off-kilter detective story. There were definitely lulls in the pace, and some passages that confused more then enlightened, but Colson really sticks with the premise and sees through his alternative universe to the very end.