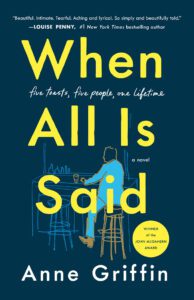

Author: Anne Griffin

Publication Year: 2019

Length: 324 pages

This is a book about growing up and growing old in modern-day Ireland. So you know what you’re in for. With just one small letter change, they could have changed the title to When All Is Sad and not lost a step. Because being a child in Ireland in the WWII-era was rough. Seems people just dropped like flies — after working the fields and/or basically being indentured servants. And it’s not as if life got much better as you moved post-war and spent years dodging alcoholism, poverty, disease and general degradation.

When All Is Said focuses on an 84-year-old widower named Maurice Hannigan. He’s had one of those Irish lives. It sounds like no fun. But now he’s sitting at a hotel bar toasting five people in his life who have had the biggest influence. And when I say he’s toasting, he’s essentially narrating his life story in his head. His non-present audience is his son, Kevin, to whom he’s conveying these stories. As a narrative setup, it’s honestly a little gimmicky. But ultimately it’s a clear and concise way to build a character study by conveying all the different players over the span of his life.

What unfolds is five love letters to mostly dead people. People who made him the man he is. Whether he likes the man he is or not is up for debate. Regardless, he is a self-made man. A man of some means and some reputation in his small burgh. A man who has formed complicated personal and financial entanglements with local families, both friend and foe. Some out in the open. Some in secret. But now, getting drunk at a bar, his life apparently on the line, everything is on the table. Is it thrilling stuff? Nope, not really. Does a lot of it revolve around a coin and a somewhat confusing relationship with this local family? Oddly, it does. It all feels very literary, but not particularly compelling.

And this, for whatever reason, says Irish to me. These small moments. These crushing moments that are so micro in their scope so as to seem very insignificant until taken on the whole. And, even then, it’s often a small people leading small lives thing. It permeates. And, frankly, it doesn’t play incredibly well when you read books like this sparingly or inconsistently. Because it reads like a bunch of shrugs strung together in this story of property deals and regret. Huh, maybe it should have been called Property Deals and Regret! No, that’s a terrible title.

Anyhow, Griffin is a decent writer. She writes in a very straight-forward manner. But one that is tinged with a little Irish lyricism nonetheless. It’s actually pretty interesting that she chose to write a male protagonist. I suppose maybe it’s not that unusual, but I do feel like sometimes when the roles are reversed, female characters end up sounding weird. And while she’s writing an obviously softened and more sensitive version of and aged man in Maurice, she does a wonderful job of capturing his voice.

Now, this thing does nosedive into melancholia, and is ultimately a real fucking bummer. I mean, there’s not a whole lot of brightness and sunshine anywhere in this tale. The dude loves his wife and his kid (in his way) and is petty in all the ways we all are. My lack of a commute has ruined my relatively steady diet of reading, but the hyperbolic nature of series television has really strained my ability to put up with the slow burn of a slow novel. It’s not Griffin’s fault, after all. It’s my brain and I’m sorry.