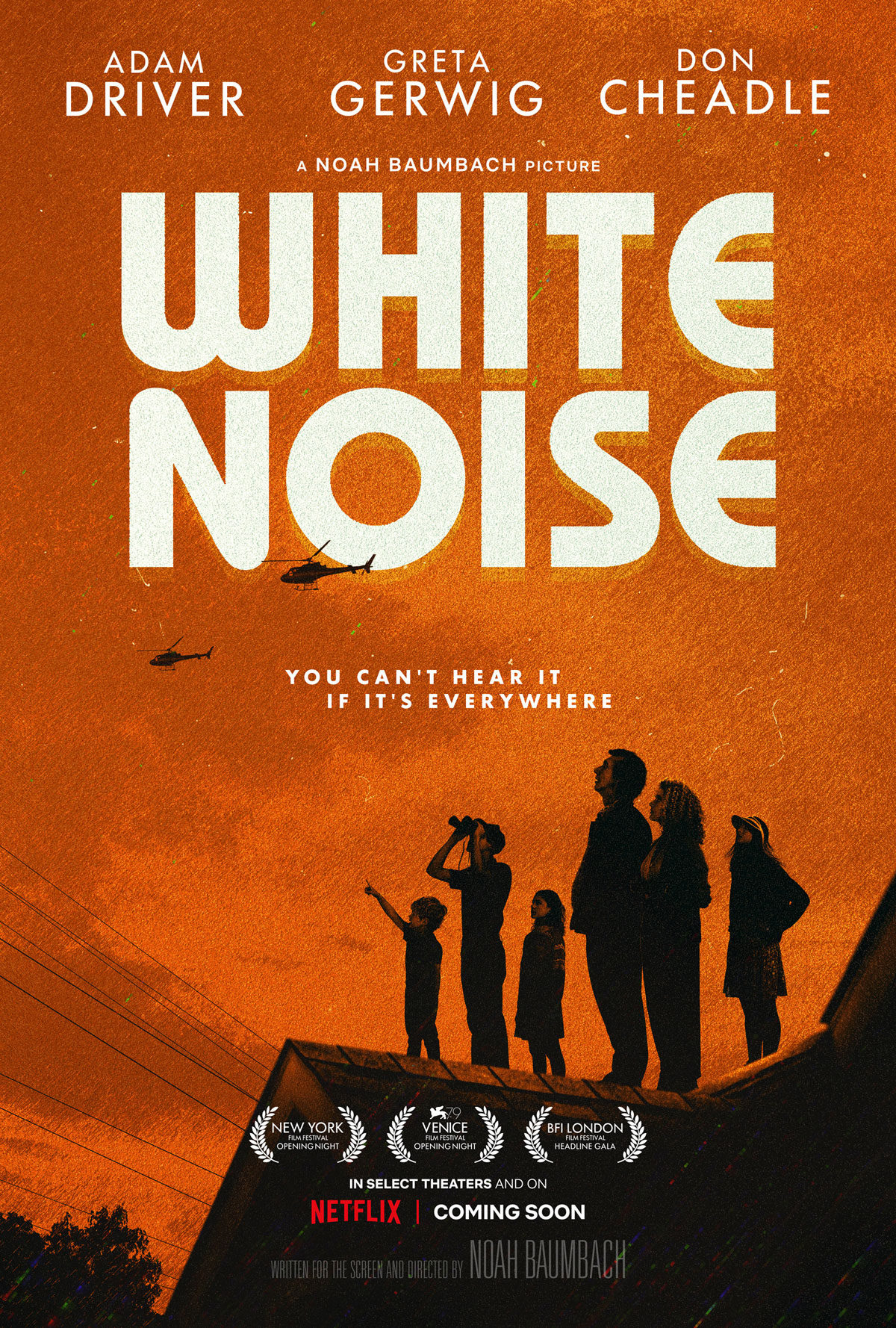

Director: Noah Baumbach

Release Year: 2022

Runtime: 2h 16min

There was a time in my life when all I wanted to do was read. It spanned the Walkman and the Discman, and even rolled into the iPod age. I lay in my bed. I stood on subways. I sat on buses. Much like this dumb site, all I wanted to do was catalog books in my head. Then I focused on cool books, eventually. By cool authors. Like Don DeLillo. Anything deemed “post-modern,” or new literary fiction that was considered hip or would like get written up in Esquire by some guy in thick-framed, black glasses. And though I probably got to White Noise seven or so years after its publishing, I feel like it was the gateway drug for me. The way to move on from a passing interest in literature to something deeper. Until, of course, truly portable entertainment came to be. And ruined everything.

So why, you may ask, do I start with all that nonsense when you’re here to ostensibly read a review of this Noah Baumbach movie? To give you context. Not to build expectations, I guess, but to tell you that this was a novel that helped shape my taste in reading over a span of more than a couple decades. To classify me as a guy who read things like White Noise and at least, at a minimum, believed he understood it. Because, in all honesty, I’m now not so sure I did. Especially after watching this film based on that novel. In fact, I don’t even really remember much of it, but I’m certain it couldn’t have been quite this disjointed and thematically all over the place. Could it have been?

Let’s place the original novel in time. The year is 1985. Reagan was president. The war on drugs was shiny and new and in full swing. We had this clown-ish dude running the country with his giant smile while military spending skyrocketed and kids were being “scared straight” about drugs, sex, strangers, black people, gay people. I know because I was alive then. Everything — and I mean everything — we were told would kill you. Touch this once, you’re dead. Smoke that once, you’re dead. Talk to the wrong person on the street, he’ll try to sell you crack and then take you back to wherever and make you a prostitute. Plus, while this was going on, they rolled back every regulation ever put in place. So while we were scared to leave our houses because something was bound to murder us, companies were free to do whatever the hell they wanted. Including running trains filled with chemicals through suburban neighborhoods. Which is not only relevent in 2023 after one term of another clown rolling back all regulations, but back then as well. And is the inciting event in the novel and movie: The airborne toxic event. Not the band, mind you, but the crash of a train filled with noxious chemicals, which causes the evacuation of an entire area in Ohio, including our characters, the Gladney family.

The film is about existential dread. I think. But it’s also about higher education. And consumerism. And the pharma industry. And the nuclear family. And ecological disaster, obviously. And herein lies the issue for me. What was relevent and biting social commentary in 1985 is not so much in 2023. This is especially true in the consumerism lane. Which is represented in the movie by the technicolor shelves of an A&P supermarket. The 27 different boxes of cereal and detergent. And, yes, I get back in the 80s that these “super”markets were somehow overwhelming in their consumer worship because we were just moving off of the more local grocery store with its humble displays. But compared to the landscape in the 2020s with its superstores and Amazons, this felt practically dinky and nostalgic. Jack Gladney (Adam Driver) playing a professor of Hitler Studies — while goofy and probably shocking at the time — is hardly anything in this day and age. The age of specialization and the study of just about everything. It just feels like, despite Baumbach most likely loving the 80s setting, perhaps should have moved this into the modern age and made some of these things feel more attached to today. Things just didn’t age well, I guess.

I would classify a large chunk of this movie as absurdist. Verging at some points on screwball. It starts off with the family, including the aforementioned Adam Driver and his wife, Babette (Greta Gerwig), and their blended family of children, all talking over each other. It’s a very stage play type set-up. Characters wandering around the same space all spouting sentences of heady overlapping dialogue. It’s kind of a disconcerting scene, but one that I suppose introduces us to the concept of “white noise.” Everyone talking, but nobody listening. Eventually the toxic cloud causes them to have to abandon the house and go to a refugee encampment with others. The dialogue continues to be that verging-on-stilted, high-intellect, but also low-intellect Baumbach thing that he does in all his movies. But, again, the satire and absurdity of the whole thing rears its head as the family drives their station wagon into a river and has to steer it through the rapids… Which I think is directly from the novel, but serves as one of those moments where you’re like, “What the hell are we doing here? Is this supposed to represent that they’re adrift, or are we just doing some dumb comedy here?” The tone and the commentary just gets ground up in these scenes that sometimes feel more real and grounded and other times feel like a cartoon version of family life. It’s confusing.

And then the thing, in act three, becomes the Alfred Molina drug dealer scene from Boogie Nights. Or the Gary Oldman drug dealer scene from True Romance. And we’re in a completely different movie. This all revolves around Babette’s hidden addiction to an experimental drug called Dylar, which is supposed to remove the user’s fear of death. But instead makes the user kind of lose their faculties and unravel in unpredictable ways. If I recall correctly, the book goes much more into the side-effects of the drug in subtle and clever literary ways, using words and metaphor to explain things. But the movie just kind of makes it the crux of Babette’s isolation from her family and sets up what amounts to a shoot out. The whole conceit of the drug feels very Vonnegut in its mechanics within the original story. Because we expect these kind of other-worldly absurd things to happen in his books and accept them as literary license to symbolize something else. But in the case of this movie, we don’t really dig in, and the pill addiction just seems like a pill addiction, the fear of dying the fear of dying and the shootout at the drug dealers sleazy den a shootout at a drug dealer’s sleazy den. And it’s all kind of discordant and chops up the movie in a way that makes it weird.

This is all to say that sometimes there are classic novels that have been deemed “unfilmable” for a reason. Novels that people revere. Novels that people read during a college break that set them on a path of cool. Like most, if not all, of both DeLillo and Vonnegut’s books. The film adaptation of Breakfast of Champions, for example. Fucking terrible. This certainly isn’t on that level, but my point is that a lot of the subtlety, tone and literary nuance can’t be captured in a two-hour filmed affair. There is too much subtext, internal dialogue and, in some cases, omnipotence in the writing to make it work properly on screen. Plus, in the case of White Noise, the era in which it came out made it feel very current. And, heading into the late 80s, almost prescient. But that story, taken at face value, feels almost a bit quaint now. It feels retro. Not only because we had to suffer through 136 minutes of Driver and Gerwig’s awful 80s hair, but because the impact and even the newness of the type of familial story being told just doesn’t hit the same now as it did back then. Even with the ending dance number. Which is cute, but nothing we haven’t seen before in everything from 500 Days of Summer to The Big Lebowski. Do yourself a favor and read the novel as a fully formed adult. I think you’ll certainly get more out of it than I did back then, and more than you’ll get out of this half-way-there movie version.