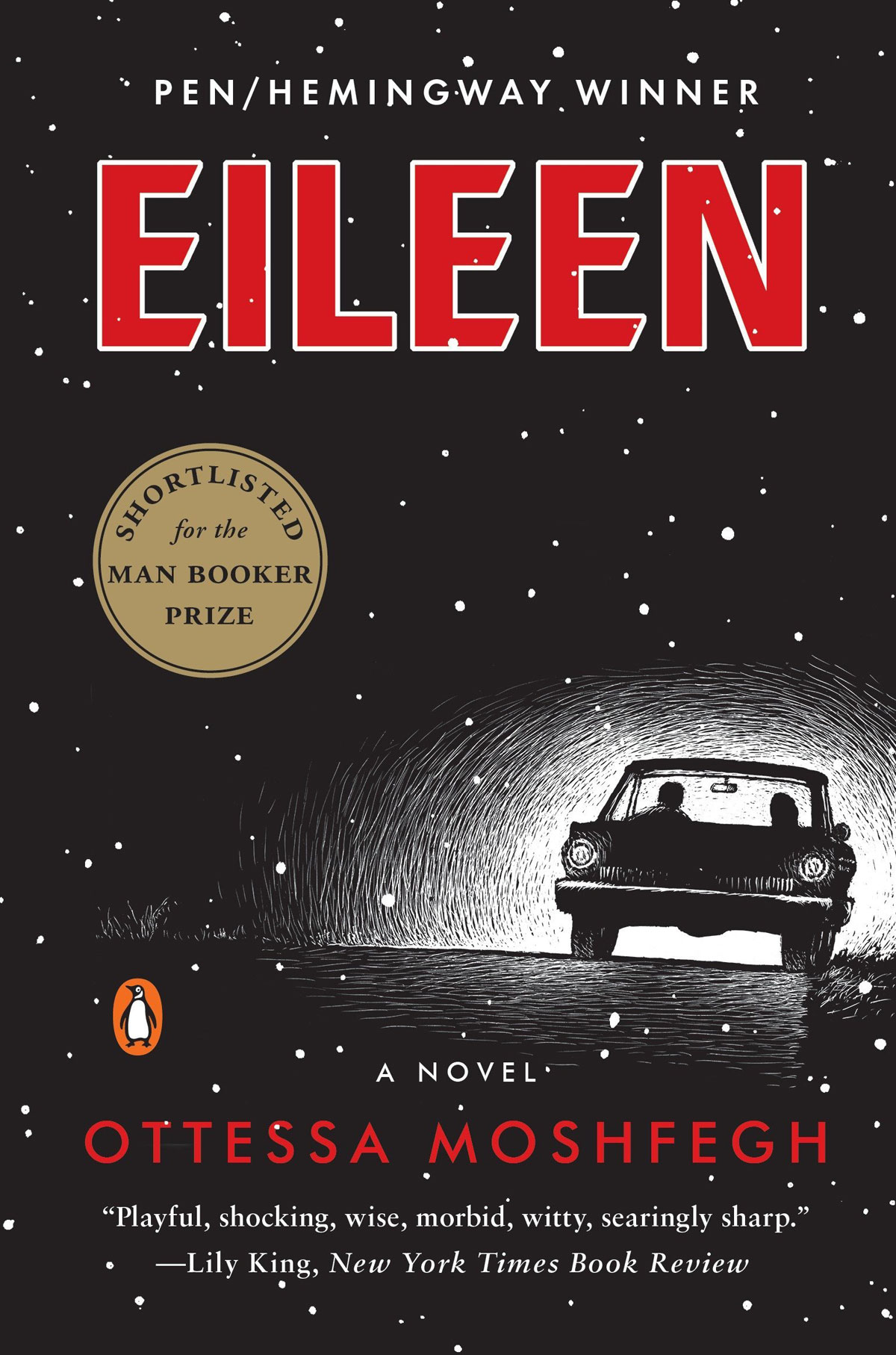

Author: Ottessa Moshfegh

Publication Year: 2015

Length: 272 pages

I came to Eileen with little to no idea what it was about. I mean, I had a vague notion that it was about a girl or woman named Eileen, but I think the title probably makes that self-evident. But it’s an award-winning novel and my cursory read of the synopsis and Moshfegh’s bio lead me to pull the trigger. Plus – and this is how I normally decide to actually purchase a book — the price, after placing it on my Amazon wishlist, had dropped to $1.99. So, win, win!

But enough about my bargain hunting for literature. Like I mentioned, Eileen won the PEN/Hemingway Award, which is an annual award given to a first-time American author of a full-length book of fiction. That seems like a long list of qualifiers, but essentially it’s given to what they feel is a promising American author of fiction. Looking back at the winner’s list, I’ve only ever read one other winner of that award, Then We Came to the End. And I liked that one. Granted, the award has only been around for… Jesus, 1976 was 43 years ago? Whew, ok, it’s been around for almost half a century. I should really check some of these books out.

Anyway, Eileen is not so much a narrative as a character study. But, lucky for us, she, Eileen, is a fascinating one. She’s a young woman in 1960s Massachusetts working as an admin at a prison and living with her alcoholic father. She’s socially awkward, wears only her dead mother’s clothes and mostly lives an internal fantasy life that involves lusting after (and stalking) a guard at the prison she doesn’t even interact with and imagining herself running away from her small, dreary New England town to NYC to live some life that makes little to no sense. She spends her days buying gin for her ex-cop father, hiding his shoes in her trunk so he can’t leave the house and sleeping in the attic of her house due to her clear masochistic streak.

It’s a pretty awful sounding time, though the book isn’t as dark and emo as it sounds. I mean, sure she stuffs herself full of laxatives and loves to sit in her own stink, but there is something about the way Moshfegh draws the character that makes her so bizarre and so oddly outsider that she becomes a curiosity and, in her own way, almost alien in her internal thoughts and response to outside stimuli. She’s written as a real human being, but her approach to things is just out there. She’s not a nihilist per se, but a sheltered 24-year-old virgin with no friends, an abusive father and no real clear anything that she loves, likes or stands for.

Until she meets the new woman at the prison, that is. The educated, beautiful Rebecca, who seems to be everything Eileen is not. Yet she, for some reason, befriends Eileen and seemingly is poised to change Eileen’s life. Or at least that’s how Eileen sees it. I know this book has been classified as a noir in some places (including by the author herself), so it struck me when reading it that the Rebecca name is also owned by the titular Rebecca in the Hitchcock movie, uh, Rebecca (which is based on the book of the same name by Daphne du Maurier). Shout out to Hipster Parents for paying for a college that allowed me to take an entire class where all we did was watch Hitchcock films! Anyhow, without giving too much away, the parallels of this Rebecca in the book — an elegant, sophisticated, seemingly perfect woman — and the unseen deceased wife in the movie, who is also all those things, but turns out to be something completely different, are pretty dead on. Granted, I haven’t seen or heard this take in anything else I’ve come across, so I’m probably utterly and totally off as usual. But my brain went there.

As usual, I’ve done a shitty job of summing things up, but I did find the book kind of fascinating if for no other reason than I couldn’t ever really figure out where it was going. That’s not unusual for me, I suppose, but in this particular case I just wanted to continue to see how this outcast’s brain worked. She’s unlike any other character I’ve really read. She’s kind of hateful, but also sympathetic, but also disgusting in some ways. She’s matter-of-fact, but also super-dodgy. In other words, a conundrum. And that, in this world makes for a good read.