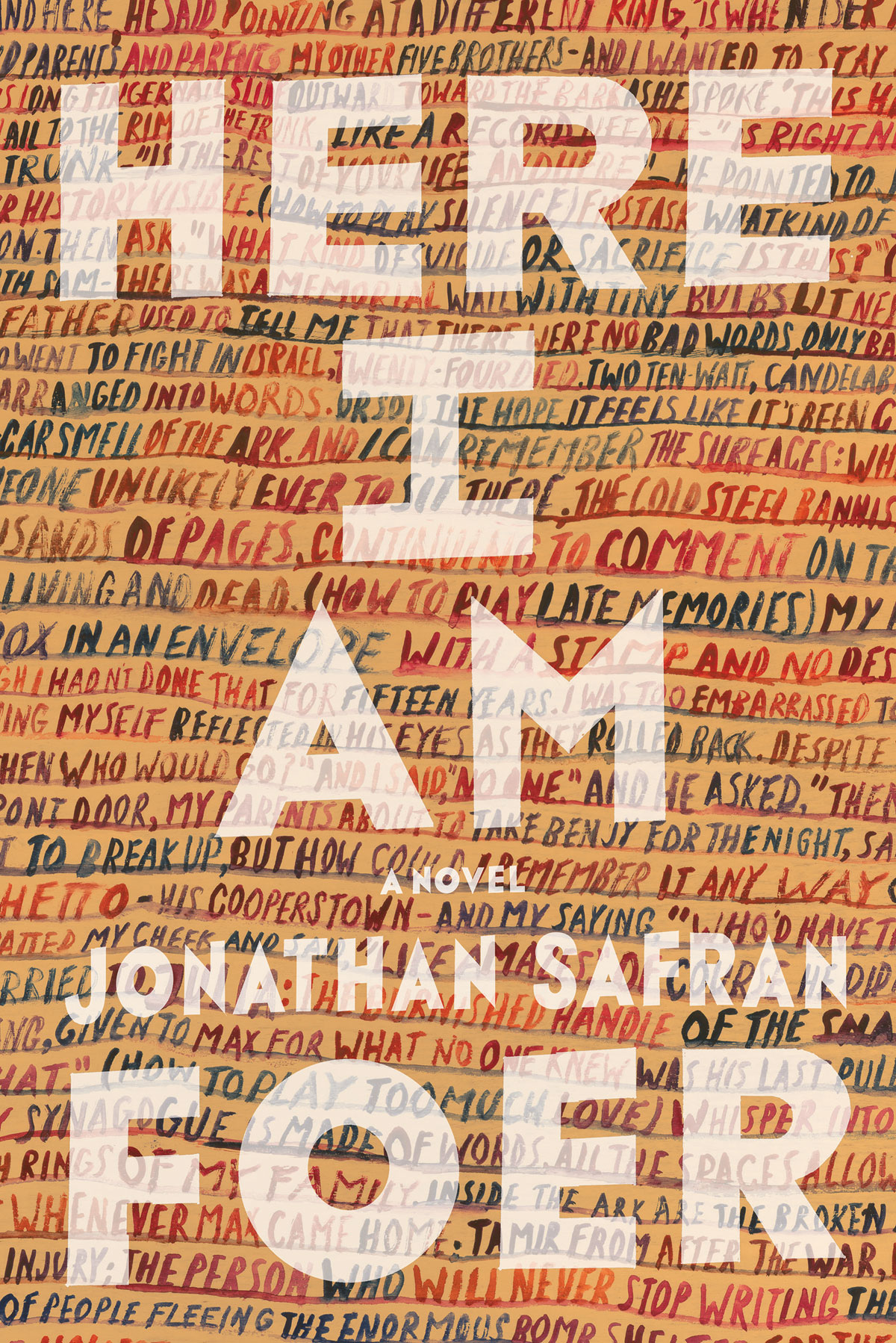

Author: Jonathan Safran Foer

Publication Year: 2016

Length: 592 pages

Look, man, I’m a Foerhead. Ok, that doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue, but suffice it to say that I’m a fan of Foer’s work and had been waiting with baited breath for him to write a new novel for eleven years since his last, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. And, for some unknown reason — maybe out of anger toward him for taking so damn long for a follow-up — I waited another year and a half or so to read this one, Here I Am, after it came out in the fall of 2016. There’s no saying why I do the things I do other than I like to build up anticipation and I’m practicing the whole try-not-to-be-disappointed game. Unfortunately I’m bad at that game and this novel ended up not playing fair.

So Jewish this book is. Like 200 times more Jewish than my bar-mitzvah and only a bit less than a Jackie Mason concert. We’re certainly used to Foer using some of the Jewish mysticism and not exactly hiding his religious background, but the entirety of the narrative here is wrapped up in that identity. It’s all embodied in his protagonist, Jacob Bloch. Jacob is a writer, of course. Because what else would a semi-veiled version of Foer be, and what kind of characters do writers love to write about more than writers? And, as with many writer characters in novels, he is a writer by trade (writing for what sounds like a CBS-like TV show), but has his true art that he’s been working on outside of work just languishing on a shelf awaiting just the right time to bring forth into the light. Jacob is married and has three children of varying ages. He has a wife. And he has angst and indecision and all sorts of neuroses that I had a really hard time connecting with. This issue is that whatever the hell is eating him is really the glue that holds what little narrative there is together. So failing to connect with him and his issues made for a bit of a slog for me.

To talk about the plot is honestly a bit of a waste of time, as it’s not really about that. There are a bunch of event-related things going on in the lives of the Blochs. Jacob and his wife’s marriage is falling apart. Their son’s bar-mitzvah is falling apart. Jacob’s grandfather is falling apart and the political situation in the Middle East is falling apart. Oh, and their dog is dying. So we have this family unit coming unglued, kind of paralleled with a fictitious explosion of Muslim/Jewish war in the Middle East that includes Foer-invented Arab alliances and entire geopolitical movements that felt immediately out of place in what was essentially a small family drama. It was jarring, honestly. I understand at some level it was done to make the cerebral argument about what being “Jewish” really means, as Jacob’s cousin from Israel happens to be visiting him in the US when war breaks out, but I feel like I could have either done with the Bloch-family version of the novel or the novel that it sort of becomes that asks the question of what it means to be a safe, secular American Jew versus one that puts his Jewishness on the line by living in Israel. But mixing the two just made the thing feel kind of disjointed.

Look, I know I’m doing a shitty job of describing things here, but the novel kind of defies description. I can only express my disappointment. I expected some wit and witticism like Foer gave us in Everything Is Illuminated, or at least something to rise above what amounts to a 600-page shrink session. It just felt like the author didn’t know what line to take once he kind of established his base, so he tried them all and threw in some global crisis in order to kind of universalize Jacob’s struggles. Honestly, I’m not exactly sure what the issue was for me. The pacing was, at times, glacial. The wife character was, at times, confounding. It seems as though Foer just used the younger children and the grandfather as occasional comic foils. Oddly, the most interesting character to me — the one who had the most complexity and was written in 3-D — was Jacob’s cousin from Israel. His struggle, which is almost the negative to Jacob’s, employs a brightness and dynamism that Jacob and his wife’s characters don’t. Sure, there are some enlightening passages in the book. Foer is a wonderful writer, and he can drop wisdom bombs when he so chooses, but the boulibase of mishigas that this one ended up being was not much more than a well-intended think piece on the state of being Jewish in America.