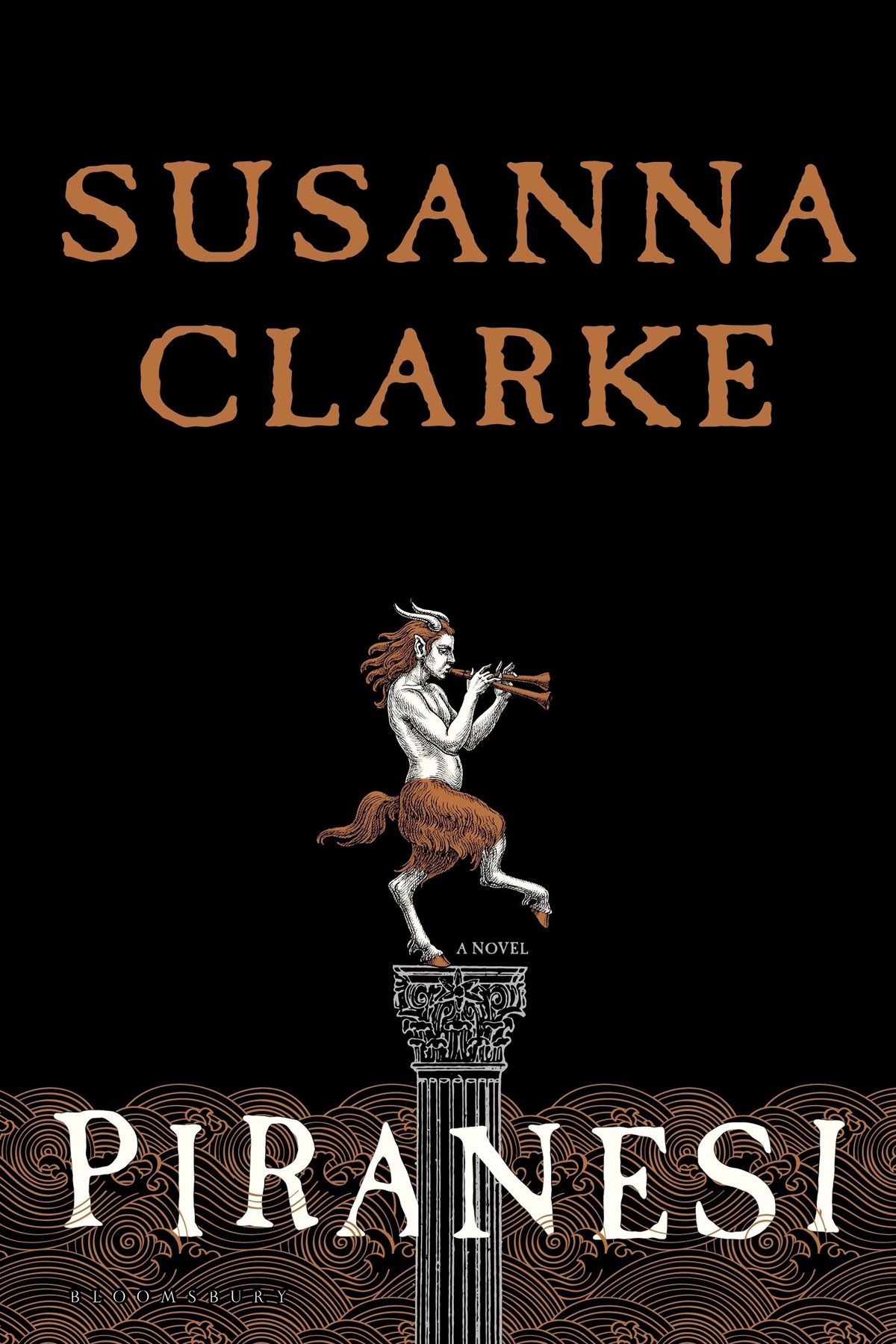

Author: Susanna Clarke

Publication Year: 2020

Length: 272 pages

I’ve truly gotten out of the habit of reading. And on some level this makes me sad. It’s not that Piranesi has knocked some sense into me, or somehow kicked off this dormant feeling in my soul. It’s not that kind of book. Or maybe it’s that exact kind of book. And therein lies the oddball, subtle nature of this tale. Part illusion, part delusion, part fantasy mystery. It’s just a really different way to tell a story, though it employs the narrative trope of what amounts to an unreliable narrator (or at least one whose memory has failed him), but set in a world completely made up by author Susanna Clarke.

We are brought into this alternative world by a narrator named Piranesi. It’s not the name he’s given himself. It’s a name that the only other living person in this world, The Other, calls him. He doesn’t really know what his name is, but accepts Piranesi because he doesn’t seem to really care. This world is a “House” made up of unending halls and vestibules surrounded by ocean, and in many places exposed to the sky. Within the House are thousands of statues. Some are classical, some just kind of weird. Additionally there are thirteen skeletons of the dead (give or take a couple; I’m bad at math). So, as far as Piranesi is concerned, there have only been fifteen people in the world, including himself and The Other. Piranesi spends his days fishing, talking to statues and preparing to give reports to The Other a couple days a week at set times about his search for the “Great and Secret Knowledge.” He journals all his daily activities and findings, using a self-made measure to mark the passage of time. Since there are no clocks or calendars in this mysterious House.

We are presented the story through these journals, and it becomes apparent pretty quickly that Piranesi has no clue about his own identity. Not to mention how he found himself in the world of the House. The Other clearly has some connection to another world — bringing him new journals, pens and shoes — but Piranesi doesn’t seem to really question it. He’s subservient both to The Other and the House itself. Honestly, I had no idea Piranesi was a man until several chapters in. There’s a certain female energy that Clarke imbues the character with. I’m not certain if that’s intentional, or just the way her writing comes off. So, we’re set up with this scenario where Piranesi, this remarkably innocent-seeming character, goes about his day talking to statues and birds, making seaweed soup and occasionally talking to The Other about their world. That is until “16” comes into their lives. Another mystery for Piranesi to solve, but also our first indication that The Other may be more of a malignant character than the naive narrator thinks he is.

Through a series of steps, Piranesi uncovers some old journals he thought lost and discovers clues about his origin, as well as the origin of the House and of The Other. The mechanics of how he comes across the discovery of the old journals and pieces them together is honestly a little dubious narrative-wise, but Clarke clearly decided that she was going to keep this story tight and not sweat the details on some things. This discovery unlocks the narrative of the book, moving us out of the day-to-day observations and painting of the world of the House and into stories about the occult and control. Not to mention making us question the nature of Piranesi’s mental state and the reality of the House itself. It reminded me somewhat of a TV series, Archive 81. But, of course, I’m sure it’s based way more on classical literature, ancient and not so ancient. Clearly there are some Chronicles of Narnia things going on here, along with the antagonist’s thirst to tap into the pure knowledge of the ancients. Get that pure philosophical juice from which all thought and smarts flowed throughout history. Or something. And, honestly, this is where I had a little trouble making sense of why this was all happening. And why living in this world gradually erased the memories of the other world. I just couldn’t quite grasp the rules of the universe, nor the motivation of some of the characters. Which I suppose is more of a sci-fi concept than a fantasy one, and I should just accept that it is what it is and that things can be a little more floaty in these universes.

Whatever my nit-picks with the narrative, the novel is incredibly original and effective in what it does. Clarke’s writing is evocative, but rarely flowery or overly-sentimental. Because the book is written in the voice of a single character through his journals, that put some limitations on how and what she could write, but she really maintains that voice throughout and injects it with some really fascinating perspectives. I think the best part about the book is that Clarke never feels the need to do what novels seem to have to do. It goes at its own pace. It speaks in this very specific way that feels different and intentional without feeling writerly at all. In its approach, it’s a much more casual affair than the massive tome, Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell. Unlike that previous novel, she leaves much more space for your mind to fill in the world and draw conclusions about characters. The ambiguity of the situation is a feature, not a bug. Also, I’m sure my visualization of the House is much different than 99% of the other folks who read this book. And my conclusion about the characters also quite different. Whatever the case, I know there is a group of readers who would really enjoy this novel for its whimsical oddity if nothing else. But I would read it again, given the chance, just to experience something new and sneakily hopeful in a general media landscape full of dark and downcast.