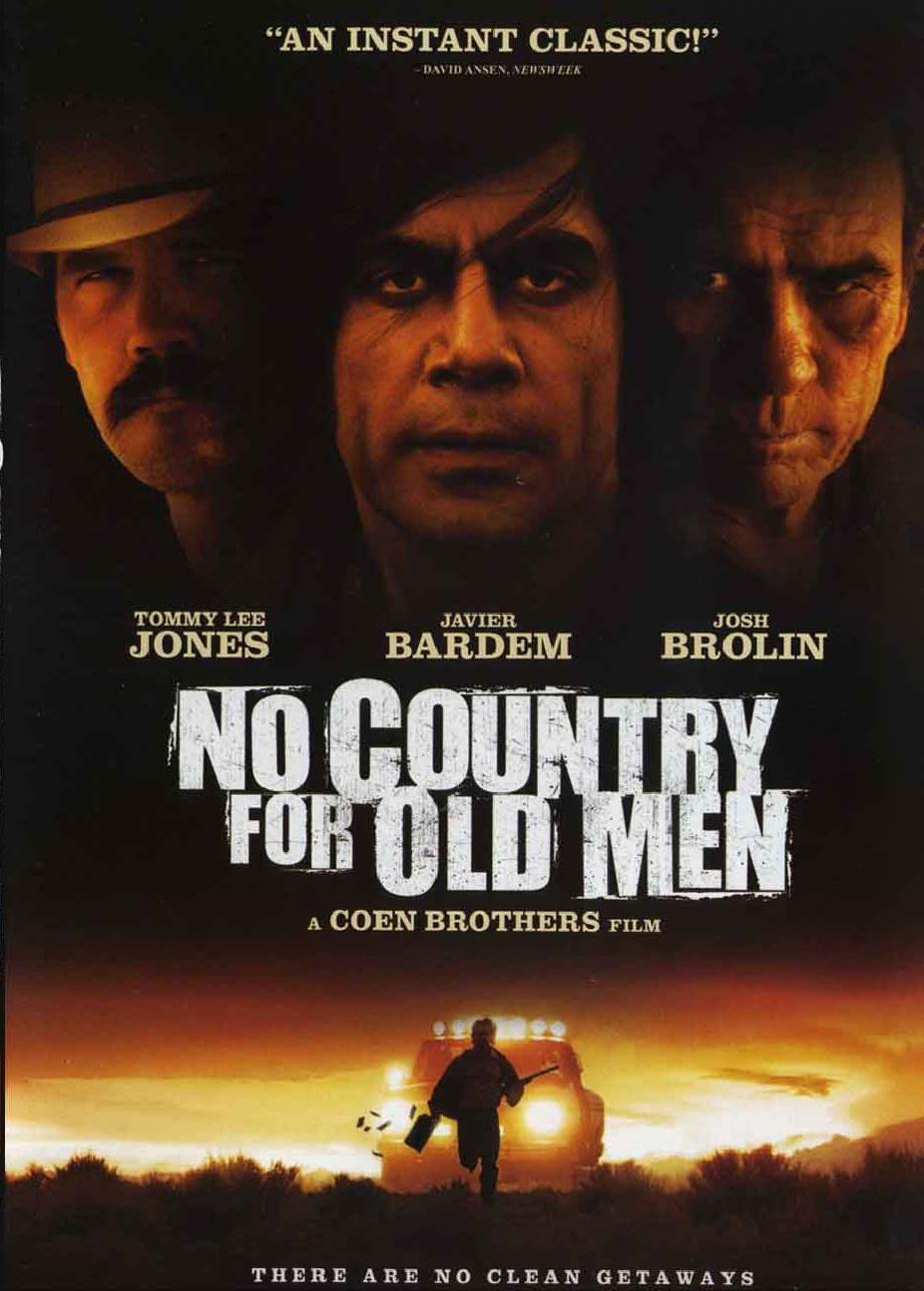

Who would have thought a guy with a Raggedy Andy haircut could be so menacing? Javier Bardem as the maniacal hitman/killer in No Country for Old Men makes the Terminator look like a girly man. And it’s all because he’s flesh and blood and not some titanium skeleton from the future who’s been programmed to kill. Well, at first Bardem’s character, Anton Chigurh, is paid to kill, and then he just sort of freelances because he thinks it’s the right thing to do.

Getting in his way is Josh Brolin, who, according to the Coen Brothers, was actually a casting mistake. They meant, or so they claimed in Esquire, to hire Josh’s father, James, in the role and set it in 2007. Because of the whole James/Josh screw up, they had to set the film in the early 80s in order to make the younger Brolin’s Vietnam Vet character and Josh’s age match the timeframe. It’s bullshit, of course, as there’s no way that crap would happen, and plenty of ways around changing the entire timeframe of the movie (making him a Desert Storm vet, for instance), and was probably just the Coen brothers fucking with Esquire in trying to build some lore around the film. Needless to say, they didn’t need gimmickry to make the thing successful. And, as it turns out, Josh Brolin can actually act! Now it seems a little more okay that Diane Lane married him–just a little.

As a downtrodden hunter who serendipitously comes across a whole bunch of money at the scene of a massacre, Brolin plays it with the perfect mix of restrained “oh my god” and “oh shit.” At first we get the sense his stone cold character is un-phased by the devastatingly violent scene onto which he stumbles, but soon we see that beneath his gruff exterior he has a weak spot for human frailty. And, of course, that’s his undoing. Especially when he soon gains an ungodly nemesis in the form of Chigurh and his weirdo pageboy haircut. The haircut that says to people, “go ahead and laugh, I dare you.”

Bardem’s character is complicated and uncomplicated at the same time. On the one hand he is a heartless killer with no sympathy or regard for human life, and on the other he is a benevolent angel of death who can spare a man’s life with the flip of a coin. It goes to the fact that all lives have the same value to him–absolutely none. Despite this, he is a man of principle. He will not give up. He keeps his word and always follows through on promises and threats. What else can you want from an assassin? Bardem plays him with an even intensity that all emanates through his crazy eyes and his clipped sentences. There’s no Jack Nicholson over-the-top crazy going on here, which would have completely ruined the understated and deeply disturbing quality of the film.

Tommy Lee Jones as the weathered Sheriff Bell who is trying to unravel the mystery of the original drug deal gone bad and the subsequent trail of bodies can’t help but play hangdog at this point in his career. The man just embodies the part of worn Texan lawman, and plays it with a tired restraint and relative resignation and ambivalence that also makes the tone picture perfect. He just seems sad, which adds to the general sense he has that the world has changed for the worse and that there’s no going back. It’s funny that it took a movie like this to put the Coen Brothers back into a Blood Simple/Barton Fink/Miller’s Crossing/Fargo frame of mind. Gone is the wackiness of O Brother, Where Art Thou?, The Hudsucker Proxy, The Big Lebowski, The Ladykillers and Intolerable Cruelty, and back is the stylized bleakness that they’re so good at. Granted, Raising Arizona is probably my favorite of their movies (followed closely by Barton Fink, Fargo, The Big Lebowski and then Miller’s Crossing) but even that movie had its dark moments. In what almost seemed like an homage to Raising Arizona’s “unless round’s funny” scene, Bardem’s character interacts with an old clerk in a desolate roadside store. It turns out to be one of most tense scenes in the movie, as Bardem literally gambles the man’s life on the flip of a coin. Obviously not round, obviously not funny.

The film, as are all Cormac McCarthy books, is extremely violent and hardly what I’d call uplifting. In fact, I had the one-two punch of seeing this movie and then launching directly into reading The Road. It wasn’t a great few days for my sunny-meter, if you know what I’m saying. Despite the grimness of it all, this film is amazingly affective at conveying a story where there really is none. Of course that’s been a trait of the Coen brothers for years. Take a simple plot that usually involves kidnapping, money or a scam or some sort and use the characters to drive the plot to its logical conclusion–while said plot often takes a back seat to the interaction of the characters. Nothing’s really different in No Country, as the money becomes a kind of afterthought (as it’s basically just tossed over a bridge into some weeds at one point), and only acts as a catalyst to bring these characters together in a battle of wills and a fight to the death. Good times.