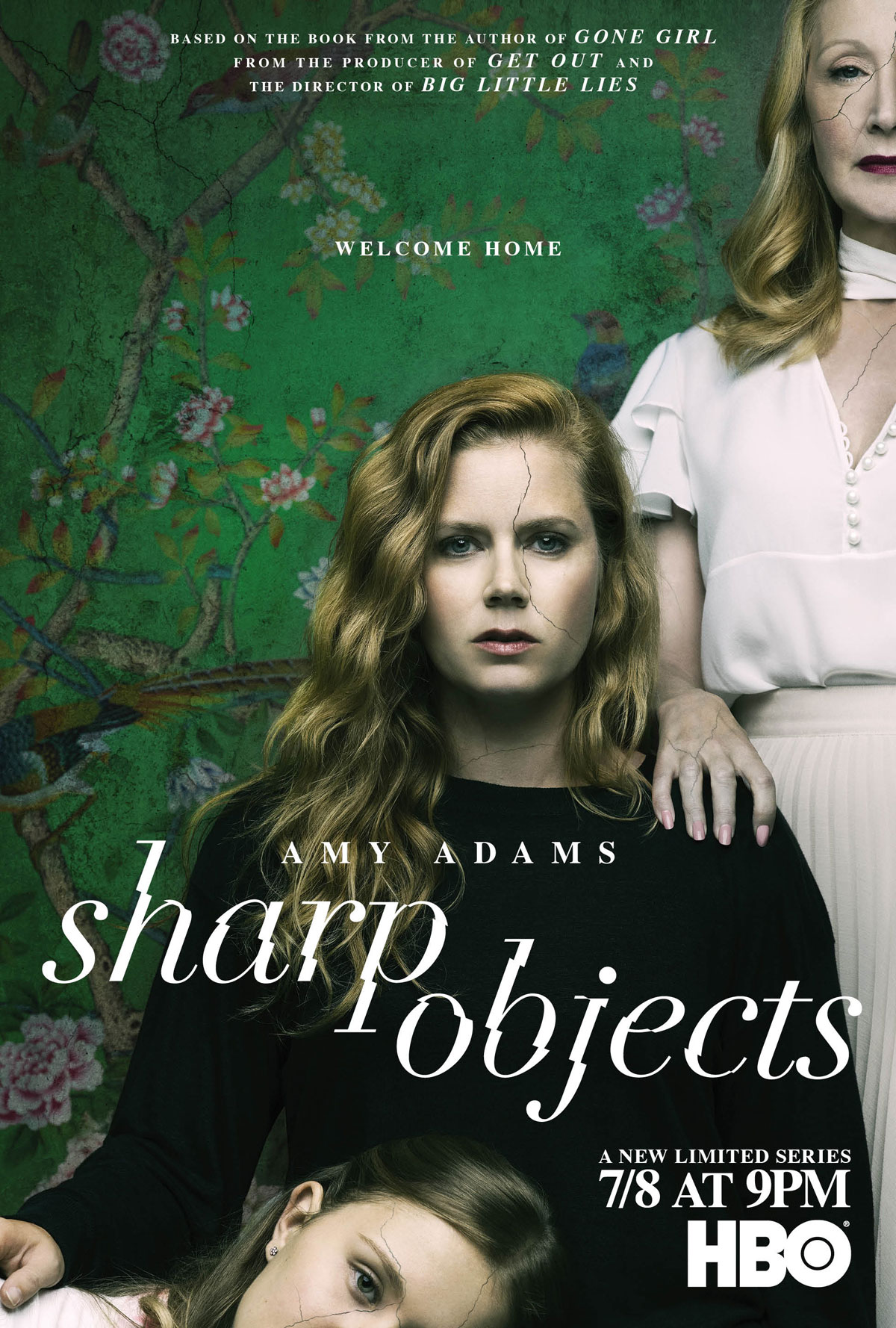

Network: HBO

Creator: Marti Noxon

Series Year: 2018

Watch: Max

Everyone in Sharp Objects is terrible at his/her job. Camille (Amy Adams) is a terrible reporter. She sleeps with subjects of her reporting and spends more time drinking vodka than writing. She also never seems to tell people she’s a reporter and never lets them know that what they say is either on or off the record. In fact, the whole fact that she’s a reporter gets lost within the first couple of episodes as she blurs the lines between objective observer and suspect. Her mother, Adora (Patricia Clarkson), is a terrible mother. She’s cold and harsh. Oh, and she also seems to be poisoning her own children. She’s also not much of a wife, as she makes her husband sleep on a pull-out in another room. The town sheriff, Bill Vickery (Matt Craven), is lazy and not particularly interested in or competent enough to solve the murders in the town. He mostly eats cereal, goes to the convenience store at the gas station, eats cereal again and drives around talking to teenage girls on roller skates. The Kansas City detective, Richard Willis (Chris Messina), who is brought in to assist the investigation also sleeps with subjects of his investigation, drinks way too much and seems to go for every head-fake thrown his way. The stepfather, Alan (Henry Czerny), is a jobless dandy who just sits downstairs playing bad music on his super-fancy stereo while his wife does all sorts of bad shit, including the stuff I mentioned above . Camille’s editor, Frank (Miguel Sandoval), is also bad at his job. A supposedly caring man, he sends his sucky, emotionally fragile alcoholic reporter back to her hometown fully aware that it could send her into full-blown crisis, but thinks that said sucky reporter will somehow become a quality employee while being submerged back in the community that caused her to be emotionally unstable and drunk to begin with. He also drinks too much. In fact, the only person who does her job well is Elizabeth Perkins, who plays the nosy, drunk neighbor. She’s great at being both nosy and drunk.

All this badness revolves around — you guessed it — a child murder in a fictional town called Wind Gap, Missouri. Camille is a big-town reporter in St. Louis coming off what we later find out is a traumatic stay in a mental health facility who is sent back to her hometown to track down the story of a whodunnit. The setup is asinine on its face, but we’ll go with it. Her family is a prominent one in Wind Gap, her mother, Adora, essentially the matriarch of the town. She lives in a large mansion with her husband and teenage daughter, Amma. I tried to do the math several times as to how old Patricia Clarkson would have had to have been when she had a kid, but gave up when I remembered that Brigitte Nielsen just had a kid at like 65. Unlikely math aside, we are introduced to the town of Wind Gap and all its Midwestern/Southern dreariness through languid shots of empty downtown streets and an almost claustrophobic sense of the town, despite being in what I can only assume is a wide-open, totally flat landscape of brown. In fact, the pacing of the show plays almost as big of a role as any character. It’s glacial. Like truly one of the slowest-paced series I’ve ever endured. There are times when you could swear you’re seeing the exact same scene for the 14th time. How many times do we need to wordlessly see Henry put the needle on his record, put on his headphones, turn up the volume and sit in his chair? How many times do we need to see lingering shots of Amma creepily playing with the giant dollhouse replica of the actual house she’s living in? How many times do we need to watch Camille go to the one convenience store to buy vodka and pour it into an Evian bottle? The answer is, as many time as Jean-Marc Vallée wants us to. And it’s a lot. None of it propels anything forward. In fact, it makes us feel as if we’re in a stasis. And perhaps that’s intentional — like we’re slowly spiraling the drain and will eventually reach the bottom — but it’s a little too much for me. And flashbacks. There are a ton, though none of them particularly clear or necessarily revealing. They come in very quick snippets, more visions than actual narrative tools. Drunken flashes of Camille’s past that sometimes bleed into her current timeline, as she interacts with ghosts of her past – I think. I understand the methodology here, not jumping timelines as is typical of prestige TV these days, but rather letting it out in quick dribs and drabs, but it eventually feels more like Valle’s Tourette’s getting the best of him, or some sort of filmmaking tic or crutch. It’s distracting at times.

Did I mention Camille is a cutter? Yes, she ends up looking like Leonard from Memento (but with scars instead of tattoos), as messages/warnings to herself. In fact, there are seemingly words, phrases and sentences, including across her back. I was waiting to find out who helped her do those (especially because they’re not mirror images) but we never get that answer. I suppose they’re just supposed to be a metaphor of sorts, but it’s a weird logic gap that bugged me. Anyway, while Camille is in town and the sheriff is busy being bad at his job tracking down who killed the first girl and trying to find a second, missing teenage girl, the second girl shows up murdered. She’s posed in an alley (which the camera ends up driving by no less than 2000 times) strangled with her teeth all pulled out. Gross. Oh, did I mention that Camille has a dead sister? Yes, her sister died when she was younger, before she left Wind Gap. Her death scarred her — both literally and figuratively. So not only has her boss sent her into a situation with a mother who is really bad at her fucking job, she’s also in a position where it’s almost inevitable that she’ll dredge up all the awful memories of her dead sister (which is shown in those aforementioned flashbacks). So, she now needs to deal with not one, but two dead girls, which just compounds her lingering feelings about her own dead teenage sister. Which leads to more vodka and more bad behavior. Meanwhile her half-sister, Amma, is roller skating around town with her two friends in what can only be construed as a weird TV plot device, or some sort of Tootie from Facts of Life tribute, going to drug parties and eventually enticing Camille into a debaucherous night of pills and booze. It’s all a bad scene.

Oh, right, there are murders to solve. So the sucky sheriff and the equally sucky homicide detective, Richard, focus in on the second dead girl’s older brother for some reason. The thought being that he seems way too upset about her grizzly murder. Uh, that’s some good detective work, boys. Camille is not so convinced, though. So not convinced, in fact, that she also decides to sleep with him. Journalism at its finest. Or dumb psychology, if you’re following the author’s logic: they both have dead sisters now, which binds them together in their sadness. Granted, the situations are completely different — one was just murdered and the other died of an “illness” years ago — but the logic there is that… I don’t know.

As you can probably tell, this isn’t going well. And, honestly, I put most of that on the director. Sure, the story is mired in false logic and an ultimately in an unsatisfying payoff, but the glacial pace, distracting directorial style and repetition kind of soured me on the whole thing. And the performances. Well, more like the performances that presumably Vallée asked the actors to execute. There is so much low-volume mumbling that alf the dialogue is rendered indecipherable. I think he went out of his way to tell Clarkson to avoid the Mommy Dearest comparisons, never really exploding or playing scenes for high drama (which is clearly what Faye Dunaway playing Joan Crawford is going to be. So instead of screaming “no more wire hangars,” Clarkson’s character literally whispers in her echoey house the entire series. So, between the Southern drawl and low timbre of her voice, it’s almost impossible to understand anything she says. I might have been better off with the captions turned on. The rest of the cast follows in a similar vein, never really getting too energized and mostly speaking in hushed tones and mumbly, drunken mushiness. I didn’t need the thing to be a shouted stage play projected to the cheap seats, but when I have to turn the TV volume up to 50 to hear anything and then have to rewind several times to make sure I didn’t miss anything, it’s not a great look for a show that presumably had enough of a budget to pay for decent sound equipment. The thing is, I know all of everything was intentional: the slow pace, the druggy performances, the dark scenes, the distracting flashbacks, the muddy sound, the logic gaps… But it doesn’t mean I had to love it anyway.