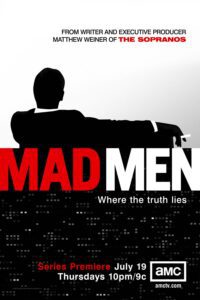

Network: AMC

Creator: Matthew Weiner

Series Years: 2007 / 2008 / 2009

2010 / 2012 / 2013

2014 / 2015

Watch: AMC+

I had an on-again, off-again relationship with Mad Men over the years. I watched the first couple of seasons live, but grew weary of the relentlessly bleak nature of the show. Bleak not in a Walking Dead type of way, but more so in the depravity of human nature the show showcased. That depravity was embodied mostly by the show’s main protagonist, Donald Draper, but even the sidekicks got into the act, boozing and cheating and in some cases even raping their way into our living rooms on a weekly basis. Like I have with so many shows over the years, I asked myself, “Are we supposed to like these characters, or root in any way for their success?” As the many Dabney Coleman series flops over the years have taught us (though I did have an odd fondness for The Slap Maxwell Story), Americans like to find something redeeming in their main characters that they can latch onto in order to get them to come back week after week to push for them to overcome their demons. In Donald Draper and some of the other characters on this show, I found little, if any, care from the showrunners about this purely American ideal of the anti-hero, who may have flaws but is ultimately doing what they do for a good reason / cause. After all, Draper’s philandering and shitting on of co-workers was done only in service to Donald Draper. His only redeeming quality being that he was damn good at his job.

So I quit the show, because, after all, I am an American and I too want to believe the fake people on television have a motivation that isn’t pure selfishness. Embarrassingly enough, that is exactly the reason I stopped acquiescing to watching Sex and the City with Ms. Hipster. I could find absolutely nothing appealing or redemptive in that bratty group of over-indulgent, spoiled clothes hounds. But while Sex in the City just depressed me about a specific class of women who lived in the same city as I did, Mad Men just depressed me. I’d walk away from each episode just wanting to drown myself in the bathtub or apologize to every woman I saw for being male. So it just became something I had no interest in exposing myself to on a weekly basis. I mean, why would I?

And then, after a couple years of not watching the show, in an ironic twist of fate, I got laid off. So this was around April 2012, right after the premier of season five. So, with some severance, and a couple months to crank on LinkedIn, spend money I didn’t have and actually look at my Facebook and Twitter feed for the first time in forever, I couldn’t help but see the insane praise for the show from friends of mine and all the media types that I follow. Did I, as a human being that was not so awesome in terms of my feelings about workplaces, want to delve back into a depressing workplace drama? Sure I did. Because whatever my feelings were about the place that laid me off, it certainly couldn’t compare to the nightmare that was Sterling Cooper and that made it okay for me to dive back in, because when you’re hurting the best thing is to watch people suffer more than you. And for some reason that logic made sense to me. The same way people who are sad and/or depressed decide the best idea is to drink. Which is, of course, a depressant. Logic. Am I right?

So I started to DVR season five while I caught up with seasons three and four. It turns out that inundating yourself not with one heavy episode of television a week, but three or four a day makes the heaviness exponential. I would finish sessions and just want to crawl into bed and pray on how the hell human beings were allowed to reproduce. The series was that affecting. But I soldiered through, at times wondering if the slog was worth it, but was somehow always compelled to continue. Because, despite some seriously glacial pacing at times and tons of Sisyphean backsliding on just about every level, there was a quality to the show that was undeniable, and a dedication to telling a story without compromise. And I had to respect that.

And then came this final season (either season eight or season 7.5 depending on who you ask) and unlike some fans out there I was fine with the series wrapping up. That is, my heart told me it was time. To this day (only four days after the finale) I’m still not certain if I was ready to have it end because all things must, or because I couldn’t bear to watch these characters who so embodied a different era slide into the awfulness of the 70s and move into a timeline that overlapped with my own. These were the guys, after all, who were middle-aged when I was a child, desperately outdated in their polyester pants and sock suspenders who hung around my grandparents in Florida. These weren’t the larger-than-life advertising titans, but the sad manifestation of a once-proud generation past their prime. This showed all around the edges of the show as it progressed, most evidently in earlier seasons when Don still donned (sorry) his hat and fat ties past when they were cool and into this season’s facial hair tomfoolery and Pete Campbell’s fledgling comb-over and just the eventual move from the classic forms of the 50s to the transient flimsiness of the ugly-ass 70s.

Then there’s the final episode. An episode that felt like it was a different show all together. A show that wanted and needed to be tidy, but ultimately felt disjointed and meandering and non-essential at times. I know Matthew Weiner, as I mentioned above, has gone out of his way to make the show defy convention and not give us what we expect when we expect it, but this ultimate hour-and-something of tv felt like a bunch of fuzz followed by a not unsuspected moment, follow by fuzz and another expected moment and on and on. It felt like a show that had already given its characters their send-offs in the episodes leading up to this one and then basically yada-yadaed final curtain calls for all of them wrangling to get to a Don Draper punchline. I know that Weiner has subsequently dismissed the cynical view of things some took with the ending (of which my view is half practical and half cynical), but sometimes people who make shows are only half right about the things they create. He sees Don’s epiphany as a new start, and his creation of the “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” commercial as an altruistic act of Don wanting to share his vision of togetherness with the world. While I, and probably 99% of the rest of the viewing public, thinking that, sure, Don has an epiphany, but that his epiphany is that his true calling is that of an ad man and that despite all of his soul searching he realizes that the thing that he became is what he was always meant to be. I can just imagine it, Don rolling into McCann with his swagger back, throwing that board up on the easel like he did a thousand times before and taking us on that narrative journey, asking us to visualize the pigtailed receptionist from the retreat and all the other melting-pot hippies singing on an ocean cliffside about a product that may just be sugar water. But why can’t this sugar water represent the “real thing.” They too have that epiphany in that same spot he did. And their epiphany is “damn, I need a soda.”

Fun fact: The character of Leonard — the man Don hugs and cries with at the end of the finale — was played by Evan Arnold, who went to my high school (and I recall being a pretty funny dude). I imagine, after seeing him for years in tv commercials and on the occasional tv episode, that this one scene may propel his career more than all the other clips combined.