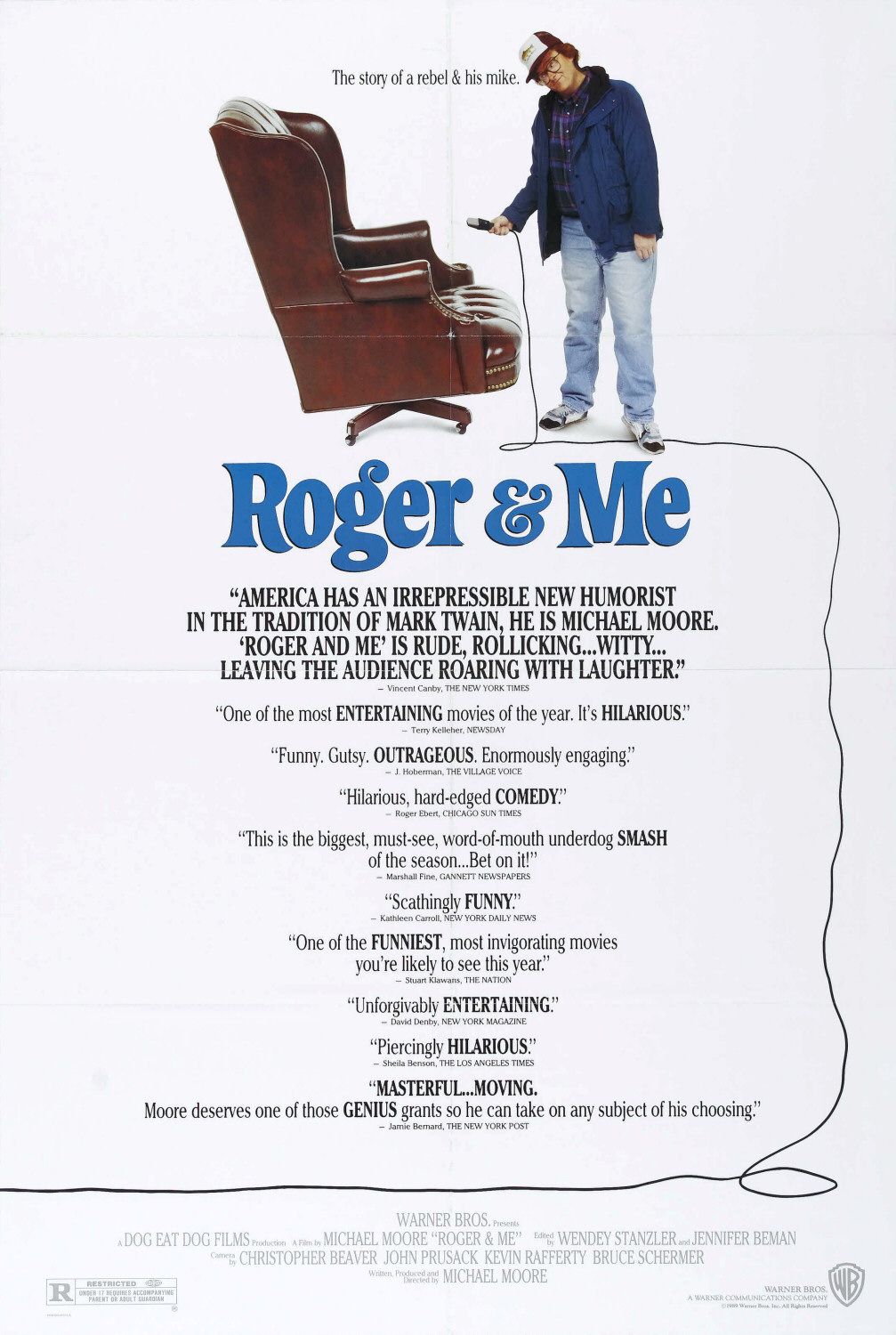

Michael Moore has been both demonized and deified. He’s almost as polarizing as the people he attacks. Some of this stems from his less than straight forward way of going after his targets. Conservatives hate to see this overweight schlub barging his way into the upper echelons. It disturbs their weird idol worship and balance of power and makes them jealous at the same time. For every person who has his eyes opened by the ”emperor has no clothes” tact, there is another that is pissed off that someone had the gall and audacity to point it out.

Despite being well on the side of pointing out hypocrisy and dirty dealings in every form, I too have my issues with Moore. There’s no denying the man makes interesting documentaries, and makes a lot of salient arguments, but he frequently undermines his own zeal by ignoring important factors by appealing to purely emotional reactions rather than rational ones. Yes, Roger Smith is kind of an asshole. He looks like a five-a-day gin drunk, and tends to tip himself very well, but the man is running a business. Moore goes after him as though he’s Dr. Evil, and has purposely gone out of his way to destroy Flint, Michigan. As if towns all around the country that relied on one industry haven’t bitten the dust throughout the history of the US.

Take a drive through upstate New York some time and see what mill closings have done to that whole area. Ditto industrial parts of PA and Ohio. The story is really less about GM and Roger Smith than it is about the death of an American town. City officials, and their wacky plans to turn Flint into a tourist destination, are almost as much to blame for the ultimate collapse of Flint as the auto industry. Smith is just a convenient villain on which Moore can hang the blame.

Are we supposed to be surprised and angry that security doesn’t let Moore up to Smith’s office, and that they cut him off from speaking at a stock holder’s meeting that he snuck into? All this aside, Moore really does put his heart into this thing. You can feel the disappointment flowing from him about his hometown. He probably feels a bit like one of those rabbits we get to watch get conked on the head with a steel pipe and stripped of its flesh.

This isn’t one of those old film strips we used to watch in third grade, or Nanook of the North; this was the new documentary whose maker injected it with all the elements of fiction they could find. Again, this is the problem, as Moore finds himself reaching at times for these elements in order to make them fit within his point, whatever that point may be. In the end, this is a fun and interesting exploration into a segment of blue collar American society, but not a great academic document about corporate greed and the devil and Mr. Smith.