This is what I would call a “quiet” movie. The tone and tenor never really changes throughout, there are no sharp edges, no abrupt turns and no conflict, really, beyond the ups and downs of human interactions.

Quiet, especially in this case, is not necessarily a bad thing. There are those older Lasse Hallström movies that are kind of quiet, but bubbling with power. This doesn’t have the understated grace of those movies, as its tone is much more ironic and comical, but it does have that cycle of life thing going on that something like a What’s Eating Gilbert Grape had.

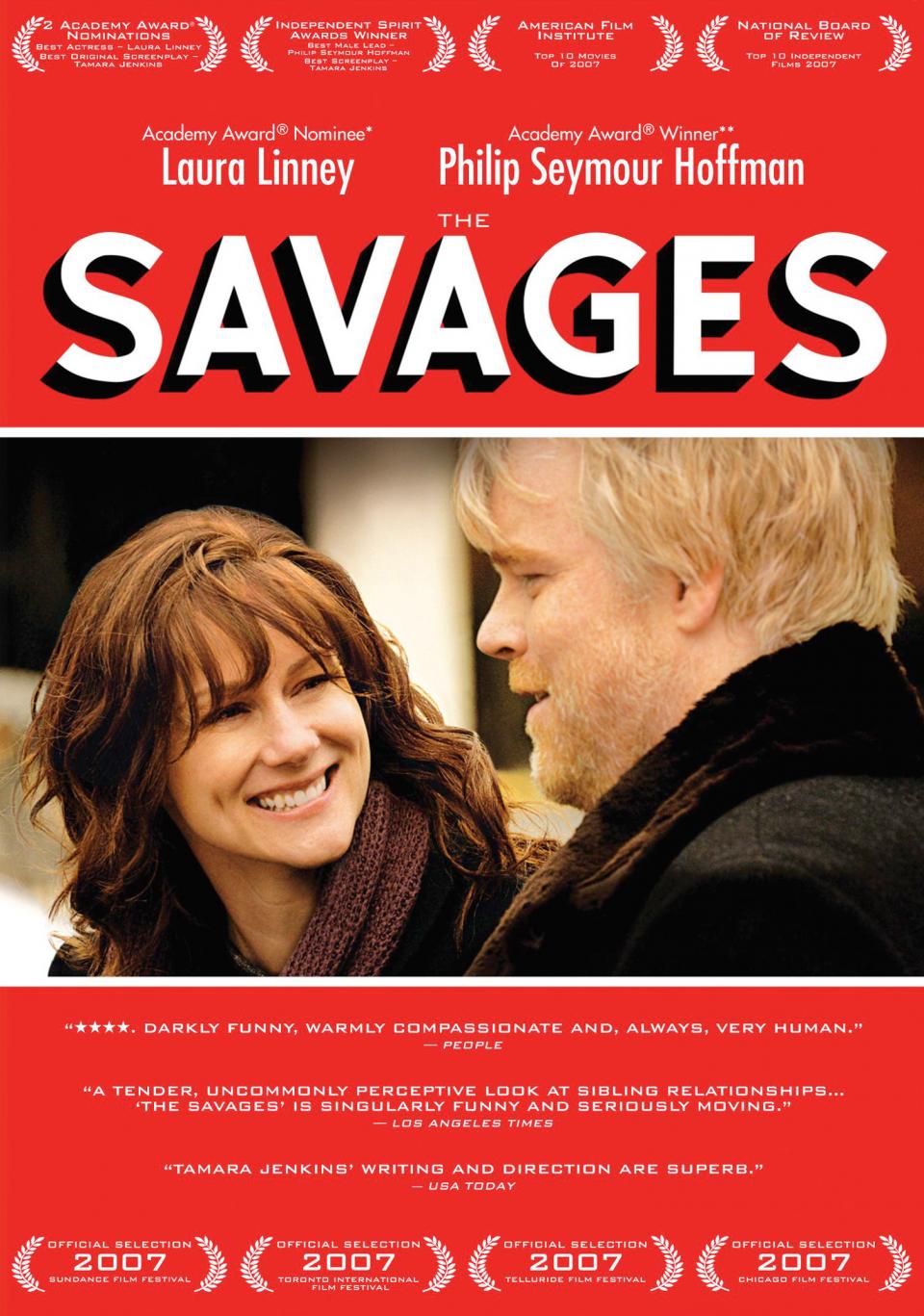

This film most certainly has the feeling that it was a stage play (although it wasn’t). The two main actors (Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Laura Linney) are on screen the entire time once they’re introduced, and their dialogue is smart and intelligent, funny, wry and poignant. Granted, Hoffman plays to type as the tortured intellectual mess, and Laura Linney does her best woman-verging-on-forty making awful life decisions misery chick. He is a theater professor and PhD (who teaches theory and history and not actual acting and stuff) at some university in Buffalo and is desperately trying to get his book about some obscure playwright done for his publisher. She is an unpublished playwright who moonlights in various lame office temp jobs and uses their stationary to send out grant applications for any and every foundation on earth. If it sounds slightly heady, I guess it is. But that’s what makes the film work. Here are these two intellectuals who are dropped into an all too human situation: having to deal with their elderly father and his decline into dementia and/or Alzheimer’s. Now the two must stop thinking about academic endeavors and start thinking about adult diapers, and, ultimately, the real life of a real person.

We do get a sense, although aren’t ever expressly told, that the father who is now in their care was not the best father in the world. He may have been, in fact, quite a lousy dad–and a downright lousy human being. But now he is their charge, roles are reversed, and it’s their turn to be kind to him in a way he was never kind to them. And how does one show one’s love to a parent while sticking him in a nursing home in Buffalo, New York? And let the dysfunction begin. The movie essentially brings the two siblings’ lives into focus. Both struggle with relationships, their jobs and just dealings with life’s daily chores. Only by observing each other do they notice the flaws in themselves. And both, in their dying father, have the common source for that dysfunction.

Linney and Hoffman are perfect as the self-absorbed, pathetic siblings. Their pitch is perfect and so is the realistic script. The writing, and the actors, don’t ever slip into melancholia or melodrama, and always manage to keep an edge to their performances. It may be intentional that these two people, who have no sense of humor about themselves, often end up, in some of the poignant scenes, laughing at each other or at themselves. As the movie progresses, the father almost becomes incidental to the plot, as we move further and further into the relationship between the brother and sister. The most interesting fact about the whole thing is that we really don’t delve into their past, into the childhood that helped shaped them into the complicated people they have become. We know their father is the lynchpin in some way–the tie that binds, but it’s only subtly alluded to throughout. It’s not until the very end of the film that we get a true sense from where their strangely co-dependent relationship comes. And it’s done in such an artful and subtle way that it really brings all of the emotion and understanding to a single, and extremely lasting, image. Bravo.