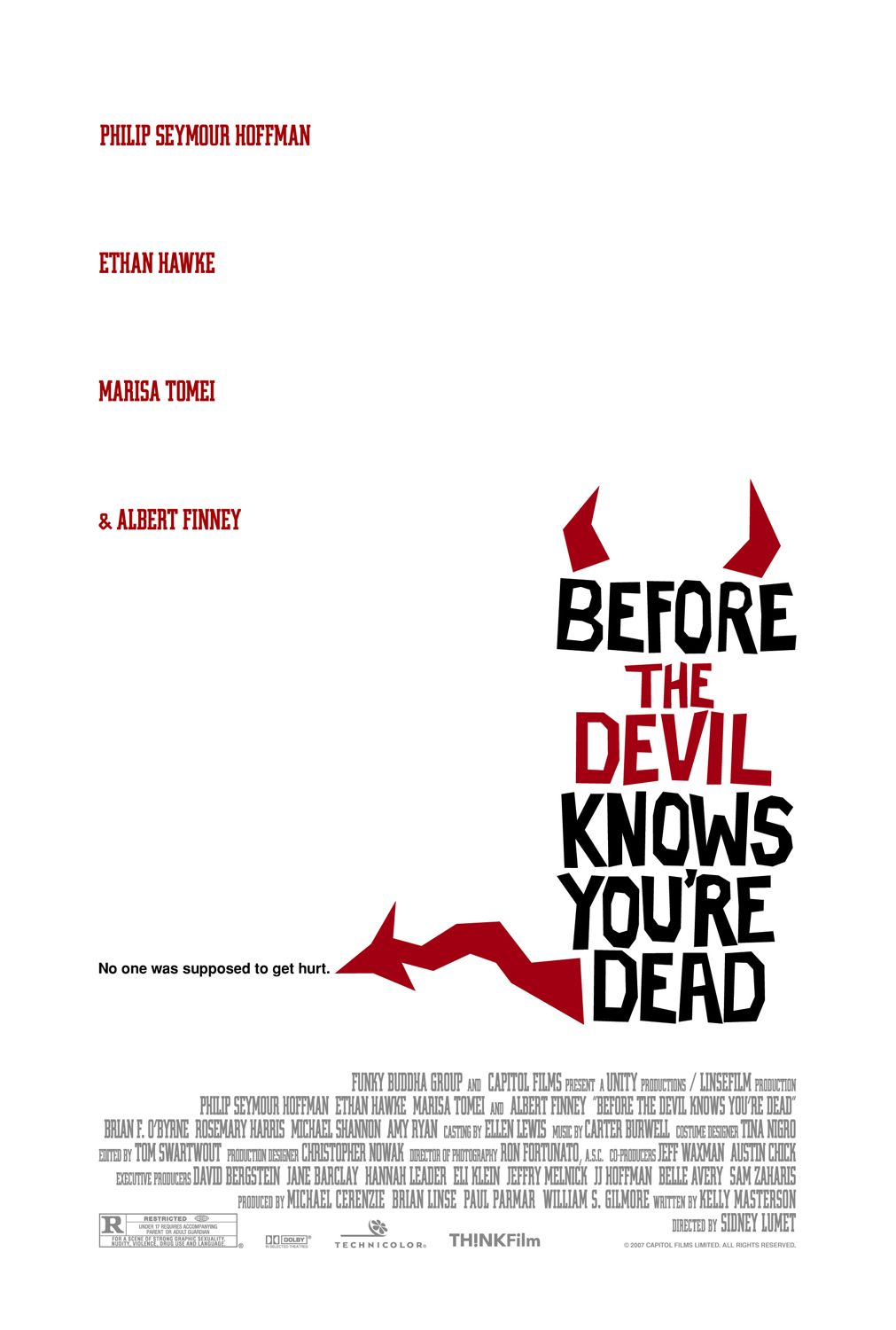

The first stumbling block here is the overly clumsy title. It’s a book title, not a movie title. It doesn’t roll off the tongue. It doesn’t shorten to a nice concise two-word blurt as you casually throw your ten bucks at the box office cashier. But it’s Sidney Lumet, so what do we expect?

Part caper movie, part family drama, part weak attempt at an 82-year-old trying to make a Quentin Tarantino movie, Lumet delivers something that had all the makings of a taught thriller with a heart, but turned into a battle of overacting, convoluted plot devices and the stench of 1980-something all over it.

The plot is relatively straightforward. You have two brothers: an older, domineering one and a younger one who snivels and cowers. Hoffman plays the bizarrely 1980s-feeling older sibling who loves the drugs, and has built up a nasty habit that has put him in a big hole. Hawke is the younger brother who has a good heart, but is a total broke mess with absolutely no self-confidence or purpose. The first thing you’re saying to yourself is, “Uh, yeah, they might as well have cast John Leguizamo and Cheech Marin as family.” I gotta say that trying to picture them as related was seriously distracting. That aside, they kind of played to type, Hoffman talking a lot, huffing and puffing and being intimidating and Hawke sulking and sweating and shaking his head and mumbling a lot. It’s clear to everyone that Hawke’s character is in deep need, as he is trying to pay alimony and child support to his ex-wife while pulling down practically nothing and living in a crap apartment. From the outside, Hoffman is doing well. He’s the CFO (or thereabouts) of a real estate company, has his own office and nice apartment and is married to a surprisingly sexy (and naked) Marisa Tomei. Why she’d be married to this slob (Hoffman looks worse in this movie than I’ve ever seen him) is beyond all of us. Especially given the fact she is actually meeting Hawke every day on his lunch break to ride him raw.

So, you have this set up. Two guys in dire straights over money, with the added element of a secret love triangle. And here comes the plot device. The two brothers’ parents happen to own a jewelry store in a strip mall in Westchester. This is a store they are familiar with and know is well insured. So Hoffman pitches the plot to his little brother that they knock over the jewelry store while this older woman mans it one Saturday morning. Nobody gets hurt, they get the money from the heist and their parents get the insurance money. Perfect! Of course, Hoffman being the fat douchebag drug addict embezzler that he is convinces his not-so-bright bro to do the actual robbery, while he just acts as the planner and eventual fence. Hawke, after much coaxing, eventually agrees, and the plot is on!

And that’s when things go all Tarantino. Hawke brings some scumbag with him to the robbery that he knows from a bar (and just happens to have armed robbery experience). He, instead of Hawke (who chickens out), goes in to rob the place. Unbeknownst to the brothers, the woman who’s normally there has called in sick, and their mother is there instead. And what an Annie Oakley type she turns out to be. A gun battle ensues, and everyone (all two of ’em) end up bleeding and dead. Bad news.

Enter Albert Finney. The man hasn’t met a scene he hasn’t wanted to eat whole. From the Daniel Day Lewis school of turning red, spitting and growling, he proceeds to overact his way through the rest of the film as the grieving and vengeful father. He’s unaware his children were the ones who got his wife killed, of course, and always seems on the verge of figuring it out. But maybe he really knows in his heart the entire time.

There is one more very Tarantino scene in which a crazed and desperate Hoffman shoots his way into his drug dealer’s luxury apartment, blowing away several people and stealing drugs and money (that are sitting in an open safe). And the rest of the movie is spent watching the family unravel. There are some taught scenes in which Finney tamps it down a bit, and we see that he clearly was very tough on his older son growing up and actually loved the younger “puppy dog” of a younger boy in Hawke better. In this wrenching discussion is the only mention of my above contention that the two actors look nothing alike–the fact the disparity in attractiveness is supposed to be obvious. The movie ends with one last shoot out and then mercifully ends in probably the only way it really can end. All dicks must die.