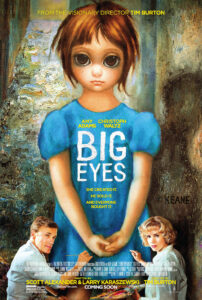

Director: Tim Burton

Release Year: 2014

Runtime: 1h 46min

I feel like I was a Tim Burton apologist for years. Well, not an apologist per se, but a fan, I guess. I mean, the man had a pretty incredible run starting with Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure in 1985 and arguably running through 2003’s Big Fish. I could have done without Mars Attacks!, but he really did have a good spate of films over that time. He established a very strong visual identity and playfulness that was there from the get-go. Granted, he went back to the same actors over and over again, turning Johnny Depp into the bizarre, non-human he has become, and in the process ruined the great actor Johnny could have been, as evidenced in films like What’s Eating Gilbert Grape and Donnie Brasco. But that’s beside the point. What is the point is that in creating these worlds he creates, he is telling a fictional story in what is, often, a hyper-exaggerated version of the real world. Sure, Edward Scissorhands could in some way be part of our universe. Pee-Wee Herman, too. Are they at the outer edges of what we experience as normal? Yes, they sure are. But they are recognizable and incredible because they are almost like aliens living among us; innocent and amazing creatures straight out of Burton’s ridiculous brain. Even when he tells a story of a real human being in Ed Wood, he’s chosen a man so absurd and on the fringe that his cartoonishness is just a perfect marriage of reality and Burton’s aesthetic.

But now, doing a biopic of a real person — a person who did a ridiculous thing but is not inherently absurd or silly in any way — he has to tone it down to make it so these people live in a world that we have to recognize as our own. But — and this is the real problem with the movie — he can hardly help himself and attempts to take a man in Walter Keane, who is essentially just a scam-artist and controlling asshole, and turns him into the cartoon bad guy that Burton feels anyone who would do what Keane did would have to be to be believed. In doing so he’s taken Christoph Waltz and miscast him so badly (even though he does look quite a bit like Keane) so as to turn an actor who has proven he can hang with the biggest stars in the world into a horrible animated idiot. First, Keane was from Nebraska. Waltz is so obviously from Europe that the lie that he’s American sinks the film from the beginning. Europe, and Keane’s fantasy about his art that reflects Europe (specifically France), plays a large part in the movie and the fact that he’s so clearly from that continent and not ours makes the whole thing seem like a farce. The dialogue he delivers is awful and is actually one of the worst bits of acting I’ve seen since some of the early Arnold movies. It seems like a joke at times and makes one wonder if Burton didn’t want to play it straight at first, gave Waltz that direction and then changed his mind in post. It’s almost impossible to watch. Amy Adams is better, but the script is hokey and almost all of her scenes with Waltz are painted with his awful brush.

The film is based on the true story of a the aforementioned Keane and his claiming credit for painting the portraits of the waifs with the large eyes that his wife was actually painting. It’s not completely clear how this all gets going, or why she goes along with it, but apparently back in the late 50s and early 60s women weren’t taken seriously in the art world and Keane thought having a man be the front for these obviously feminine paintings would somehow be a better idea. Looking at the art and looking at this guy, it’s amazing that the ruse ever worked, but it did. And it became an incredibly lucrative business, as Keane may not have been much of a painter, but he was a really good marketer of his wife’s artwork, turning them into posters and postcards and anything and everything under the sun. Apparently these things were all the rage back in 60s and I have a vague recollection of seeing them around, but they were ubiquitous. Well, as any scam go, it can’t last forever, and we see the situation deteriorate and the Keane empire start to crumble when Margaret Keane, the real artist, starts to grow a conscious, or at least becomes aware that her husband may just be a giant douchebag.

I watched this movie just hoping that there would be a shift in tone at some point. Like we were living in this lamely-scripted la-la world and then all of a sudden the drop would come and we’d be tossed into a new script where people talked like real people and the goofiness subsided. While there may have been some dark-ish moments in the film (like PG-dark), the thing overall had a gloss and weird commercial sheen on it that made it feel almost distasteful in its treatment of Margaret in particular. I kept trying to tell Ms. Hipster that perhaps Burton had gone deep on this one and had purposely woven artifice and artificiality into the film as a larger statement about commercial art (of which Keane’s were the apex), but after finishing the film I figured out that there was no there there and that perhaps Burton’s star was beginning its descent in the night sky.