Director: Charlie Kaufman

Duke Johnson

Release Year: 2015

Runtime: 1h 30min

Do you like to watch puppets fuck? I mean, not in like a weird way. Like in a cinematic, artsy way? Because, if you do, Anomalisa is your kind of film. And not at all weird. Well, it’s like Charlie Kaufman weird, but not in like an agalmatophilic way or anything. But beyond puppet sex, this film is amazingly affecting for those of us who have human hearts and human minds. It’s a very human story, after all, of loneliness, aging, depression (or at least how I perceive it) and Kaufman’s usual mix of self-doubt, doom and gloom and a good dash of egoistic pure bizarre energy. This is categorized as and mentioned in most listings as a comedic movie, but I didn’t find a single thing funny about it. I mean there were a few little quirky scenes that could elicit an uncomfortable, ironic smirk, but beyond that, this thing is as dark as a funeral shroud.

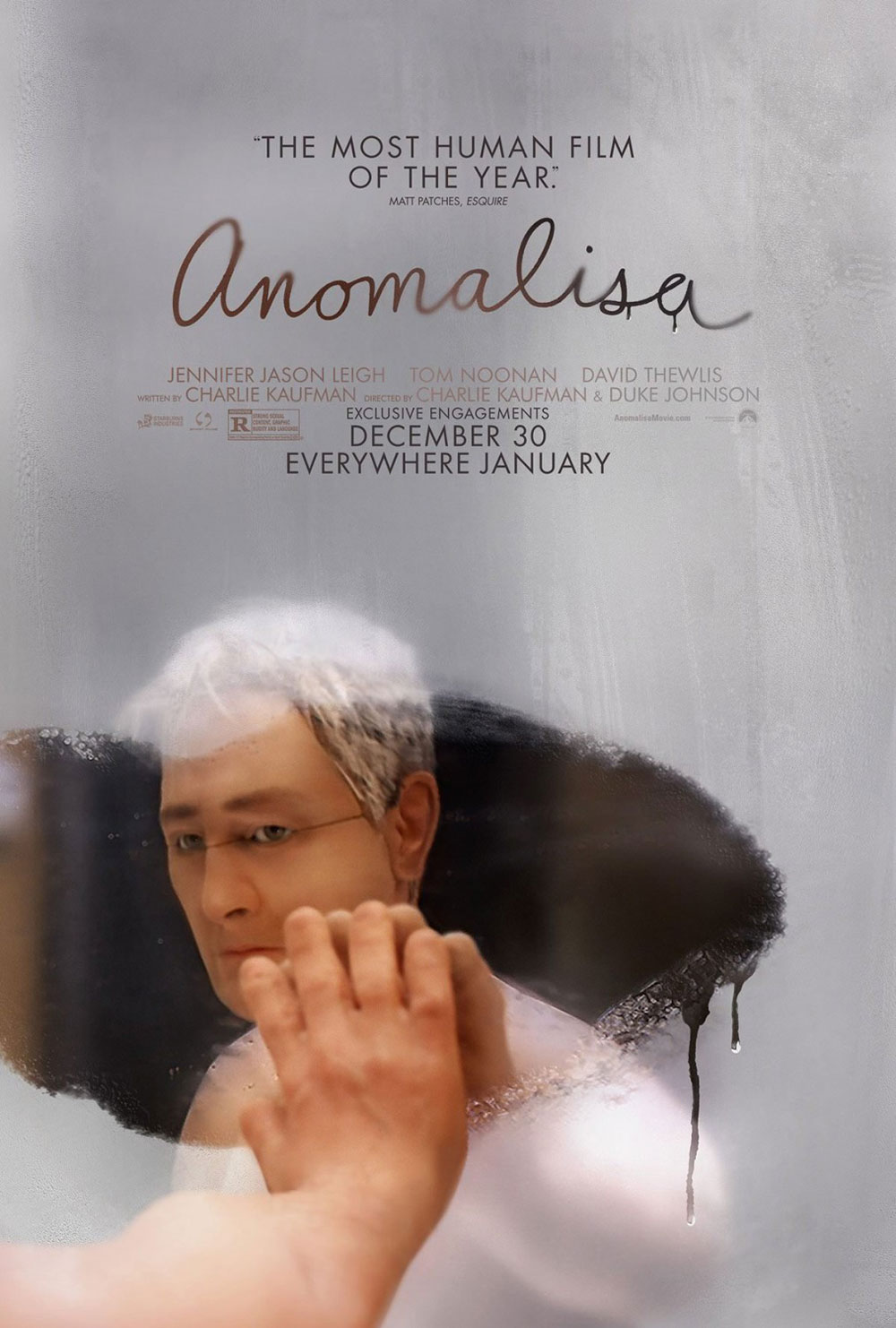

In a sad hotel in a sad city (sorry, Cincinnati, but we gotta call a spade a spade) Michael Stone — customer service expert — is set to give a talk to other customer service industry professionals at what we have to assume is a customer service conference. In this industry circle, he is — or at least he perceives himself to be — a rockstar. A middle-aged, pot-bellied, khaki-wearing rockstar. It’s unclear how his audience sees him from their point of view, but he literally sees everyone else as the same person. Their hair and clothing varies, but when we see others from his perspective, they all have the same face and the same voice. That’s easy to portray using identical puppets, of course, and the voice for every single character (male and female) — save the English lilt of Michael himself — is voiced by the flat accent of Tom Noonan. Plot-wise, it’s pretty conventional to have a main character who is beloved by others and thought of as this put-together human being actually be a complete mess. And this sticks pretty closely to that convention. Stone is insecure with his position as a customer service prophet or guru, drinks too much, is a general neurotic mess, is a seemingly poor judge of others and is not entirely perceptive (which is illustrated by his confusion in mixing up an all-night adult “toy” store and a children’s toy store where he might buy something for his young son.) The thing that separates it from your typical version of this tale is the surreal, delicate way that Kaufman can spin a yarn. There’s nothing in the way of bombast or bravado — in fact, very little happens at all beyond the mundane. But what does happen — the attempt to reconnect with an old flame, ordering room service, showering, drinking from the mini-bar — is entirely, and probably intentionally, boringly normal. Characters he encounters never abbreviate anything or speak in anything but stilted, formal voices. In fact, there are times where I seriously questioned if I’d made a mistake putting this thing on — but found myself mesmerized by it nonetheless.

And then along comes Lisa. Lisa, whose face actually looks like a different face. And whose voice (Jennifer Jason Leigh) sounds like a real woman’s voice. They run into each other in the hotel bar and Michael is instantly rapt. He is fascinated with her, the scar on her face and her voice. The thing is, there is absolutely nothing unique or intriguing about Lisa, save Michael’s perception of her. She is not particularly beautiful (granted, all the puppets are kind of potato-shaped). She’s not particularly smart. She’s not even very interesting. She says this out loud to Michael, but he ignores her protests and questioning of why he, the famous Michael Stone, would choose her. The thing is, he focuses his bordering-on-obsession over her purely on his view that she is somehow special because she actually appears to him as different than everyone else in the world. Whether this is some sort of mental illness or the manifestation of depression, it’s unclear, but we get a view into the quick-developing relationship between the two of them, which is clearly driven by whatever is wrong and/or missing with Stone. The result of this relationship and its devolution into badness is pretty much inevitable and watching it is almost excruciatingly awkward — and somehow not made less skin-crawling by shifting human emotion from a flesh-and-blood actor to a 3D-printed puppet.

I’ve had a hard time wrapping my head around this one, much like another Kaufman film, Synecdoche, New York. After it ended, I kind of sat there watching the credits roll and felt like I couldn’t, or didn’t want to, move for fear I would lose the string. This one isn’t quite as weird or esoteric as Synecdoche, but the lingering feeling it leaves you with is certainly almost as strong. And that’s an incredibly impressive feat for a movie that employed dolls to tell a very small story about not much of anything.