Release Year: 2017

Runtime: 1h 17min

There was once a band called Jawbreaker. Not to be confused with the candy or the 1999 Rose McGowan movie. They were once what we called “punk,” but in the age of Green Day we took anything that had pop leanings (and, worse, pop aspirations) and made them into pop-punk. That became a bad word after bands like blink-182 came around, but I could give two shits what you called them, Jawbreaker were good. As they say in this documentary, they were three guys with bachelor degrees playing music. The insinuation there being that priorities for a couple guys who went to an exclusive LA private school and went on to earn BAs from NYU might be a little different than a group of dudes who reveled in the idea that gutter punks were cool and dentistry was for suckers.

And, like most music documentaries, these priorities went on to be their downfall. Or, rather, their struggle between doing the “right” thing and doing the rational thing led to their downfall. Because back in 1993 when their seminal album dropped, “selling out” was still a big deal. Like if you were living hand-to-mouth and had to absolutely hustle and beg, borrow and steal just to get your albums recorded, it was considered an insane and suicidal move to court, or even talk to, major labels. It’s not as though your audience isn’t allowed to go out and be ambitious in their careers, but for punk bands at that time to show any type of upward ambition was a no-no. You were expected to pick an audience and stick with them until you turned to dust on that stinky-ass stage around the corner from your apartment, or wherever. It’s an absurd expectation, especially for guys who were ambitious enough in their lives to get a degree and maybe read a couple books here and there.

So, as the band says, this is a rags-to-riches-to-rags story. The story of a band that started with two friend in high school and continued with a third member until their steep decline right after signing what would be their death sentence at a major label. Not that the band wouldn’t have imploded anyway, but the pressure of remaining punk exacerbated what was already a contentious situation.

Taken from a group of interviews in and around 2007, including a reunion of sorts of the band at their old SF studio, we are brought through the genesis of the band in the words of the guys themselves. It all has the typical beginnings (save the college and stuff), with a couple teenagers who loved music, but didn’t really have proficiency on their instruments. They practiced and played to shows of their friends. And then very small audiences of, again, mostly friends and family. Until they recorded an album on a small indie label. And the audiences stayed small. And they thought about calling it. But instead they moved from LA to the Bay Area and found their natural fit. So the crowds got a little bigger. And they saved enough to record another album and became regulars in a scene that appreciated their energy and their increasingly good music.

And then it was like 1993 or so and alternative, grunge and punk music became super-fashionable. And they put out an awesome album called 24 Hour Revenge Therapy. And interest grew. And they played to bigger crowds and they even toured a bit. And then they hooked up with this little band called Nirvana. And everything in their little San Francisco bubble went to shit. Because touring with the world’s most popular band, even for just a few dates, was somehow a bad thing. A sign that they had outgrown their fans and would imminently be signing with a major label. There is a clip of lead singer, Blake Schwarzenbach, telling a jeering crowd at one of their local club dates that the rumors that they were going to sign with a major label were bullshit. Problem was, it wasn’t bullshit. And a week after that little speech, they signed to Nirvana’s same label, DGC.

The thing is, Jawbreaker was a band that felt very local. I’d probably only heard of them because they went to Crossroads high school in Santa Monica, about two miles from where a I grew up. And I happened upon a used Bivouac CD at the Moby Disc in Santa Monica, liked it and asked the dudes who worked there if they knew about the band. Of course they had, because they had heard of everything. But beyond serendipitous discovery and their local SF fans, I’m not sure there was much of a wave in the music world when they signed on the dotted line. But I guess that’s what selling out was all about. It was an affront to the “true fans,” but to the rest of us it just meant that maybe they could afford some better equipment and a van that didn’t break down every week.

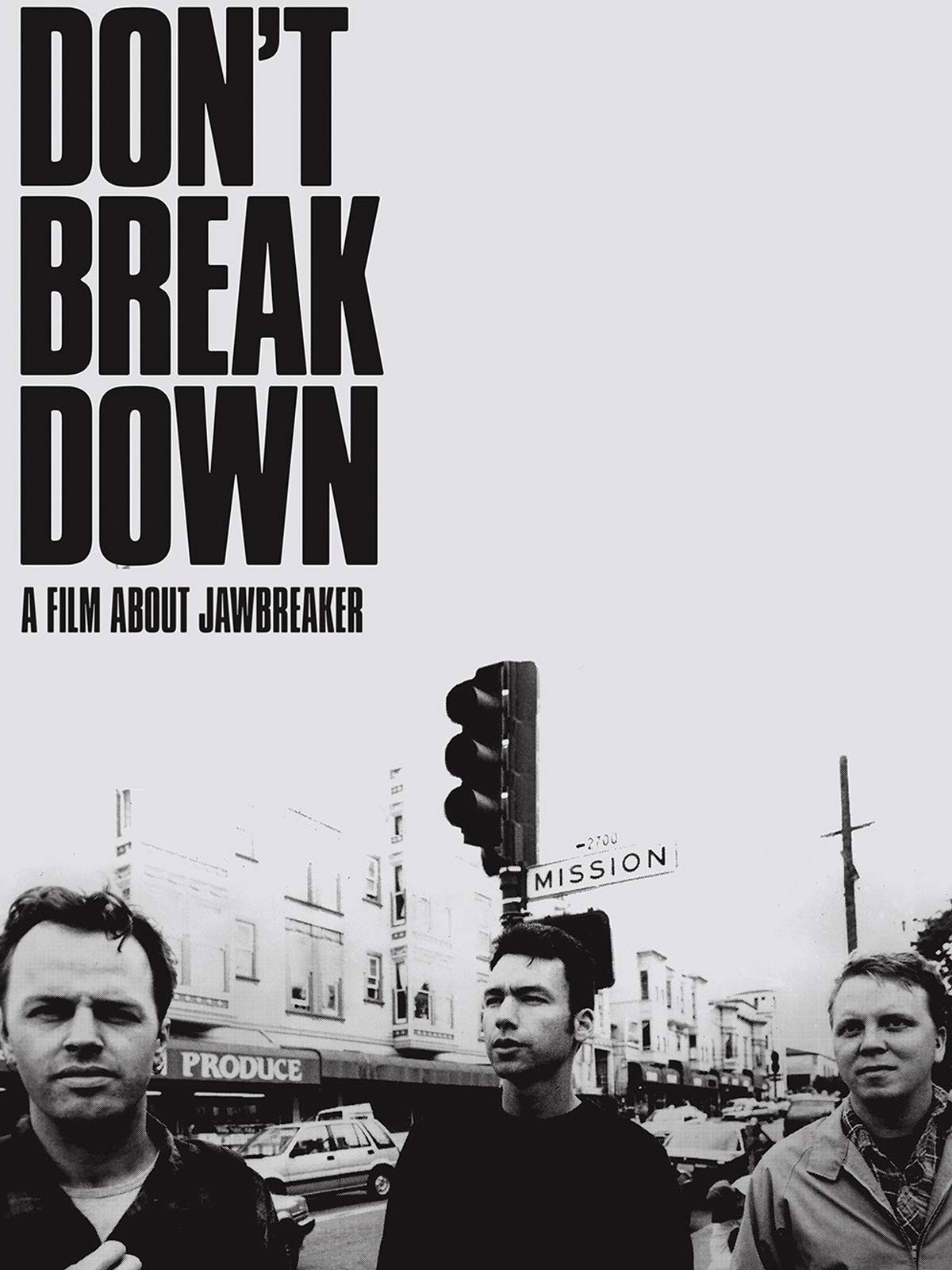

In the documentary itself, it’s very clear in their 2007 reunion that Blake and bassist, Chris Bauermeister, did not like each other. Blake was super standoffish and Chris is a this weird, manic dude who clearly liked to push buttons. Drummer, Adam Pfahler, seems like a super-normal dude who was Blake’s good friend from high school and just wanted to hang out and jam. In fact, both he and Chris were down to get in the studio space and play some songs, but Blake demurred on camera for the most part. Presumably much to the filmmaker’s displeasure. Blake also passed on explaining his thought process on certain songs because he said that pulling apart that which is magical to fans as a whole kind of ends up diminishing what made it good. In other words, nobody wants to take their favorite things and get a peek behind the curtain. Because all that’s back there is a dude making sausage. I kind of got it.

The person who actually ends up looking the most dickish in the movie, though, is Steve Albini. I’ve professed my love for his producing in the past. He produced 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (by far there most loved album) in three days and when interviewed for the film literally had to be reminded which band they were talking about. It went something like, “Oh, wait, Jawbreaker? Not Jawbox? Jawbreaker… Yeah, I don’t really know any Jawbreaker songs.” Which was kind of a kick in the nuts for everyone who loves that album, including myself. And, yeah, I know it was a long time ago (and the same year he produced In Utero), but he didn’t even produce Jawbox shit, so wtf? He did eventually recall a couple small details with some prodding, but the only thing he mentioned is that he made Blake play his guitar through what I think was like a toy Marshall amp you could probably buy at Hot Topic.

Anyhow, the final nail in the coffin was the resulting album, their major label debut called Dear You. I remember seeing the video for “Fireman” on 120 Minutes on MTV (which is probably the first time I actually saw what the guys looks like in action), but it certainly didn’t get any mainstream radio play or anything really besides scorn from just about everyone. Once again, I bought a used version of it at Moby Disc and thought it wasn’t all that bad at the time. Granted, I wasn’t a die-hard. I didn’t turn over the CD, see DCG and bail. After all, I had bought Weezer’s Blue Album from that same store a year before and they were on Geffen/DGC and I didn’t hear a single word from anyone about how it sucked just because it was on a major. And therein lies the tricky thing. If you build an audience who expects the DIY thing out of you, they will always expect that out of you. And any turn away from that aesthetic is considered a betrayal. But if you spring from the Earth a fully-formed major label band like Weezer, nobody has a care in the world. It’s very fucked up. And just to prove it, Dear You sold like 40,000 copies and the label promptly dropped them and took the album out of print. Within a few months of that they broke up.

Rags. But, of course, like all good 90s acts, the boys have found their way to forgiveness. They have played some reunion shows in the past couple of years and are on the docket to play more in 2019. I read somewhere that they’re actually writing new music. I’m not too sure that’s a great idea. Anyhow, this little doc is a nice time capsule for those of us aware of, and fans of, their music. But, beyond that, there’s not a whole lot to get excited about. There aren’t a lot of lurid details. Very little in the way of drug abuse, reckless behavior or anything illegal. On the Behind the Music scale, I’d rate it a Huey Lewis and the News. It’s just a group of three people who spent too much time together and started to not like each other. And a cautionary tale that often times your true fans are the best barometer for what you should and shouldn’t do. Because music fandom is a passion that runs hot, but take advantage and they’ll turn on you faster than you can say sell out. Even if you’re doing the thing that makes the most sense in the world.