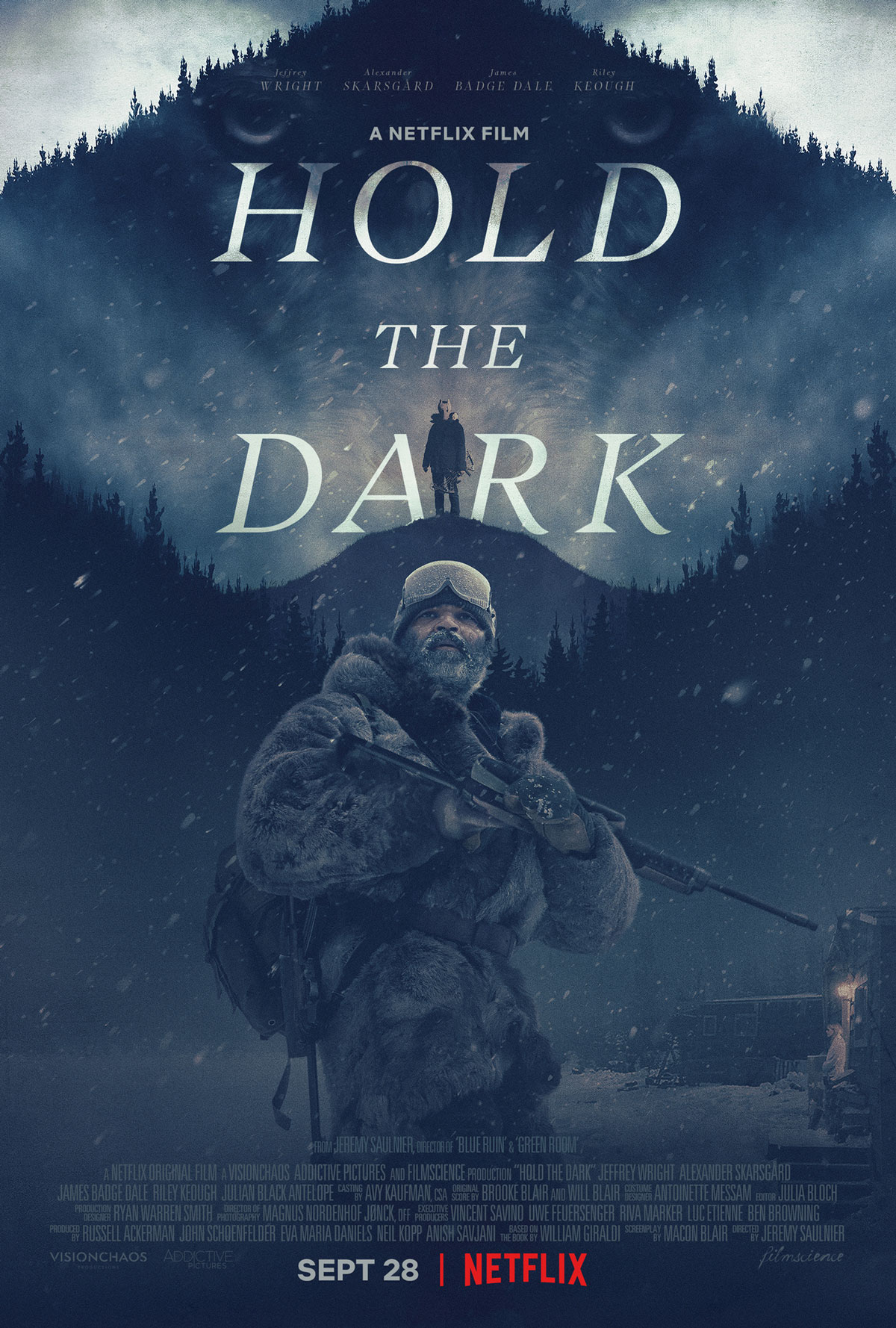

Director: Jeremy Saulnier

Release Year: 2018

Runtime: 2h 5min

Man, I’m super-torn about Hold the Dark. Well, not torn so much as confused. It’s a literally dark movie filled with symbolism and lots and lots of wolf stuff that is both very on the nose and also kind of obtuse. As I’ve said in many of my reviews, I’m terrible at catching things in the moment. All the under-the-surface symbology and subtext in films generally flies right over my head as I’m watching them and only comes into focus after the credits have rolled and I have a second to digest and consider. I’m usually too focused on the plot and making sure I don’t miss anything to concentrate on the deeper meaning of things. It’s probably why I tend to like pop structures in my music rather than the experimental ramblings of Kid A era Radiohead.

Which is why I was confused at the fact I was actually tracking with what seemed like really over-the-top paralleling of our lead characters and their other wolf selves If I, a person who is slow to pick up on stuff, is rolling my eyes at the obviousness of it all, that’s a bad sign for those more astute film watchers who followed something like First Reformed from minute one. It helps, I suppose, that the plot here is very straight forward. And they jump right into it. A woman, Medora (Keough), in nowheresville Alaska claims that her son is taken by wolves while her man, Vernon (Skarsgård), is away fighting in Fallujah. She writes a letter to wolf expert, Russell Core (Wright), to come to Alaska to track and kill the wolf who took her son. The whole setup is a little hinky and done in a pretty rushed way, but I suppose they needed to move on to the action.

Which brings us to Iraq. We leave the cold-ass land of eternal night and are dropped in a fire fight in the dessert, where we see Vernon blow away some insurgents, kill one of own men with a knife as he’s raping a local woman and then take a sniper bullet to the neck. Lots of visceral, up-close violence that tracks with us throughout the film. But just as soon as he’s whisked away by a medivac helicopter, we’re back in Alaska and its frosty environs. Thing is, this compacted timeframe — which is a little dubious if you really plot it out — somehow squeezes in the one adventure Core takes to track the wolf pack (which he finds on his first trip), the revelation that Medora’s son wasn’t in fact taken by wolves and Vernon’s miraculous return after rehabbing for his bullet wound not at all. When he makes it back to his house, Medora has already left and is on the run after her son’s true demise is discovered.

Enter the obviousness. Medora owned a wolf mask that holds some weird power when she puts it on. Core was hunting wolves. Now she’s on the run and Vernon is back and hunting her, the wolf. Did I mention that Core saw a pack of wolves killing and dismembering one of their own pups? Yeah, that. The next large chunk of the film involves one giant shootout between the “city” cops and one of the villagers, a native American friend of Vernon’s whose child was actually (but probably not actually, if you listen closely) taken by wolves that reminded me of First Blood that director, Jeremy Salunier, must have realized. Maybe it was the cold setting, the outsiderness/pain of the character, or the fact he used an M60 to mow down the cops, but there was a distinct parallel for me. Meanwhile, Vernon tracks Medora, essentially murdering everyone who gets in his way, to reconstitute his pack. We get a bit of a side story about Core struggling with his own family stuff, but generally he’s an observer and a tracker of wolves/people-wolves. But he’s also a friend to the wolves, not intending to fight or kill them, but to observe, study and understand them. So you understand that there are actual wolves and then there are people who are substituted for wolves in the form of Medora and Vernon (and to some extent their dead son, Bailey. Bailey wolf sounds like Beowulf, which brings to mind Grendel. So maybe Bailey is, in fact, Grendel and that’s why he had to die? See, I told you I don’t interpret things well… But aside from the Grendel thing, I don’t think I’m far off that the child, whom his mother refers to as being “sick,” died for a reason that is never specifically uttered, but relates to the film’s title.

So, Saulnier is one of those of-the-moment directors. His thing is that he’s good at making you feel like you’re in the setting of the film. And he definitely does that. Alaska is dark and cold and unrelenting. And this film feels that way. He also really doesn’t shy away from graphic violence. He could show a guy get shot and go down, but instead the guy gets shot right in the face and we get to see half his head get ripped away. A guy could get stabbed in the stomach and die, but instead he takes a giant hunting knife to the skull. There are no less than three instances where a dude gets hit in the neck with a projectile and either starts to, or does, bleed out as his heart pumps blood from the wound. It’s pretty gruesome, but does indeed feel realistic. I couldn’t really tell you how he directs actors, as there isn’t a ton of “acting” in this movie. The dialogue is relatively sparse, mostly delivered by Wright in his very low-key mumble, or from Keough in a weird, poetic, but stilted dialect. Skarsgård does more shooting and stabbing and psychotic glaring than anything else.

I know they tried here. And I can imagine filming this thing was a bitch. But it just feels like too much of the focus was put on the planning of fire fights and the look and feel of the film and not enough on the human qualities of it. And this may be a side effect of me watching too much television, where they have at least eight hours to flesh out backstories and feelings and motivations, and not enough movies where those things have only one quarter of that to develop all of these things. Or perhaps I’m right and not everything works on every level as it should just because it doesn’t.